A few months ago, I happened to see an image online which showed a section of a window designed and created by Margaret Agnes Rope (1882-1953). Despite having lived in Shropshire for more than 20 years, I had never heard of Margaret Rope, who was born and worked in Shrewsbury, and is now acknowledged as the greatest artist ever to have been born in Shropshire. I was very taken with the beauty of the natural scene and the contrast of the sinister beasts creeping around it. I sensed a great imagination at work in these images and felt stirred to respond. Since then I have had the privilege to become the poet in residence at the Heavenly Lights exhibition of Margaret Rope’s work at the Shrewsbury Museum & Art Gallery museum website

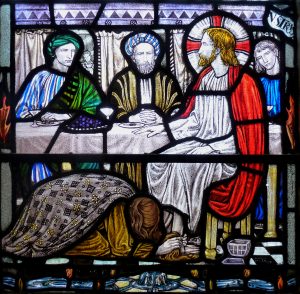

Margaret Rope was one of the finest stained glass artists of the Arts & Crafts Movement, although she has never been famous. Her work is characterised by jewel-like colour, fine painting, an ambitious vision and incredible detail informed by meticulous research. The Margaret Agnes Rope Project is attempting to make her work better known, and has made available on their website (https://margaretrope.wordpress.com ) a great deal of fascinating information about her life and achievements, which I need not replicate.

Suffice it to say that Margaret Rope (known as Marga to her family) had an independent and sometimes rebellious spirit from an early age. Stories of her exploits on motorbikes, sleeping out on the roof in all seasons and being falsely arrested as a spy give an impression of an indomitable person of great individuality. In her late teens, after the death of her father, Margaret, along with many other members of her family, converted to Catholicism. At the time Catholicism was tolerated in British Society, but much frowned upon. As a result of this conversion, Margaret, her sisters and her mother were written out of her grandfather’s will. There was not much money for the large family, and Margaret knew she would have to earn her keep.

It was unusual then for women to become stained glass artists, and it still is. It is a very demanding art form, dominated for centuries by men, perhaps because of its association with monasteries. But Margaret found an art school in Birmingham which accepted women, and from there, she ploughed her own furrow in the second generation of the Arts & Crafts Movement.

Margaret Rope’s art was inextricably entwined with her faith. She made windows for all kinds of places of worship, but her masterpieces were, in the main, Catholic topics created for Catholic churches, such as Shrewsbury Cathedral. In 1923 at the height of her powers, she chose to enter an enclosed order of nuns, the Carmelites, and lived within the walls of the convent until her death. She was able to continue her production of stained glass, but not to see the windows (which were installed in countries around the world) in their finished form, except the few which were made for the convent chapel.

A fascinating woman. A great artist. But I have become especially intrigued by the stories behind the art. I’ve had a life-long interest in mythology, folklore, religious stories, and also with the representation of animals and the natural world. Margaret’s work is packed with symbolic details, similar to the highly decorated margins of medieval illuminated manuscripts. The space in her windows is teeming with life; many species of birds, flowers and trees painted with remarkable accuracy. And like me, she seems to have been fond of dogs (I found seven representations of dogs in the exhibition).

The intertwining of images of great natural beauty with scenes of death, cruelty and sin gives the windows authenticity. They never claim that faith is easy, nor that it will lead to a life of pleasure and goodness. Margaret did not shy away from the difficult topics, including the painful deaths of the catholic martyrs and other saints. In her windows, we see darkened streets, bleakness, the devastation of broken relationships, as well as the prosaic details of life, the importance of daily rituals, candles and procession, to bring light.

So in a nutshell, I have found ample scope for my poems and some fascinating characters in this exhibition including: Judith and Holofernes (woman who seduced and decapitated an invading general), Goblin Market (the decline and near death of a young girl after yielding to supernatural temptation) and St Francis of Assisi (a rich man who leaves everything for a life of extreme poverty and is able to speak to animals).

The other topic which comes back time and time again in Margaret’s work is that of war. She lived through both World Wars and ironically received many commissions due to the death toll of the First World War in particular. Stained glass windows were the memorial of choice for wealthy families whose sons had been killed. I wonder how Margaret felt about this uncomfortable causal relationship between death and suffering, and her own livelihood.

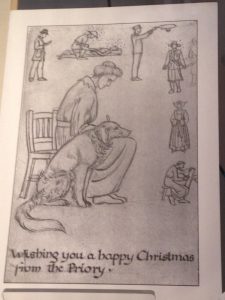

I was particularly touched by an early Christmas card she drew from The Priory, the family home in Shrewsbury, which is exhibited in one of the glass cabinets.

In it we see a central figure writing or drawing, with the family dog at her knee. Around them, the members of the family work in various ways to help the war effort. It is hard to put myself in the place of those who struggled through one devastating war, only to be confronted with another a generation later. The devastation to society, as well as the individual psyche, is something I shrink from but also feel the need to understand. Especially now, as the rhetoric of far-right groups seems to intensify every week.

In this poem, one of the nine currently displayed in the exhibition, I try to think myself into that Christmas time, one hundred years ago during the war. It has brought home to me how lucky we are to have lived during a time of peace. And how fragile that peace is.

Tidings of War

What can comfort in time of war?

Only the way a pencil line

stays fixed – can trace

a gasping stretcher

or a searchlight’s arc –

ordering the dark.

And for those who sit waiting

on cold chairs,

keeping a window lit

to welcome others home?

Only the weight of a soft muzzle

on the lap, alive and warm.

Only the escape of service,

the brain-haze of heat,

a hat’s fragile shade,

un-blistered feat,

for those who work in rust-red

fly-ridden fields.

And for those who lift and carry,

who hold the cold hand and cry

at the way the world

has launched itself,

like a thin-spun ball of gas,

and set a match

and hurtled down to its own destruction,

while some men just watch

and warm their hands?

There seems none.

But we must not hide,

we must not snuff out the light,

so here – I send you hope for peace

this Christmas-tide.

Kate Innes

The exhibition is at Shrewsbury Museum & Art Gallery until the 15th January 2017.

Sister Margaret’s Memorial