The Story behind the Story

(This was originally written as a guest blog for ‘The Story behind the Story’ by Dr Gulara Vincent)

I recently became an independent author, publishing The Errant Hours, an historical novel set in the 13th century.

The process has been rather similar to childbirth, but with a lot more coffee and alcohol.

In fact, it was giving birth that profoundly changed me, allowed me to write more freely and engendered this medieval tale. At least that is part of the story.

The other part is about adoption. For most people reading The Errant Hours, it is a fast-paced medieval adventure. But for me it is an exploration of what it is like to long for a child, and to bring up a child who is not yours by birth. And it is about the passion and danger of bringing a baby out of yourself.

My husband and I tried for children for a long time before deciding to adopt. We felt very positive about adoption, generally and specifically, because my father was adopted as a baby.

And we went into adoption with our eyes open, as a GP and a teacher. We felt we knew roughly what to expect from children. After all the necessary hoops were jumped through, we were very lucky to be able to adopt a beautiful four-month-old baby girl.

How different it is when you are a parent; how much better and how much worse!

The powerful love when you are caring for them and watching them grow, and the despair when things do not go the way you expect or demand.

Undaunted, we adopted again, a boy this time, also four months old. We had excitement and exhaustion in equal measure. It was a great gift to us, being parents of these two wonderful children.

Then when James was one year old, I noticed I was feeling quite odd.

Not myself.

Weak and a bit sick.

And so, there it was. I was pregnant. After the disbelief and joy, I was scared.

How would I cope with three children under four years old?

Was I too old for it to go well?

How would my body and my mind manage labour?

And my fears on the last point were not unfounded. The labour did not go well. It dragged on and on for days, making me sick. I had to be put on a drip. I had to be induced. At one point it seemed the doctors were about to rush me to theatre.

In the end John was born, whole and well, and I was left feeling that somehow victory had been snatched from the jaws of defeat, and life from the mouth of death. It was clear to me that if I had lived at another time in history, I would have died in labour, and my baby boy with me.

The incredible feeling of having brought a life into the world, and for it to have been so great a challenge, so close a brush with death, set me on the path to write about a time when childbirth was the most dangerous of all activities. I was interested in it physically (what herbs were used to ease labour?) and spiritually (how did people prepare for childbirth, and how did they cope with the death of their babies?).

I had studied archaeology at university, so I was used to digging into the habits, beliefs and messy remains of past cultures.

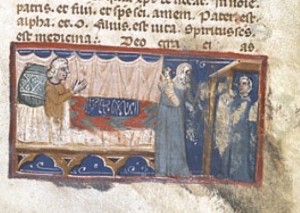

I was researching the practices of midwives in the birthing chamber on-line, when I came across it. British Library MS Egerton 877 – The Passio of St Margaret, 14th century. I read the translation of the text, I read the fascinating explanation of the manuscript and I knew straight away: this was the touchstone of my story, this special manuscript. https://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/TourKnownB.asp

In medieval times saints were appealed to for all manner of problems. Usually they were given job descriptions based on the stories of their martyrdom or miracles. Many people know of St Jude, the patron saint of lost causes, and St Christopher the patron saint of travellers. Well, St Margaret of Antioch was the patron saint of childbirth.

According to the legend of her martyrdom, Margaret was a virgin saint in the early 4th Century AD, who had converted to Christianity against the wishes of her father, a pagan priest. She was abducted by the Roman Governor, who wished to ‘marry’ her. She refused. He had her tortured in numerous gruesome ways. While this was going on, she was attacked by the devil in the form of a dragon. The dragon swallowed her, but when she made the sign of the cross it burst open and she came out ‘unharmed and without any pain.’

It was this line in the manuscript that immediately struck me ‘illesa sine dolore’. The word ‘illesa’ is medieval Latin meaning ‘unharmed’, and it became the name of the heroine of my book.

The legend says that, before she was beheaded, St Margaret promised safe childbirth to those who read the story of her Passion. And so books telling of the horrible torture of a virgin became a birthing aid. The number of such books penned in the Middle Ages was innumerable. We can get some sense of how popular St Margaret was by the number of churches and other buildings dedicated to her. But this small well-worn Passio is a rare survivor of the change in birthing practice from the Renaissance onwards.

The manuscript’s illustrations, particularly the one on the final page, depicting the saint standing with hands raised, are also of great interest.

British Library MS Egerton 877 folio 12

This is my description from The Errant Hours:

“Whenever Illesa opened the book of the saint, the feeling was always the same. She became a hawk lifted high in the air, and with the hawk’s eye she could see the sparrow in the hedge and the fearful beasts at the edge of the world in an instant, and all the detail of their beauty and horror.

But the last picture in the book disturbed Illesa. The image of the saint was smudged, and the features of her face were like a reflection seen in the water at the bottom of a well. Ursula said that many women had kissed the saint, smearing the paint in their devotion, for as she had come out of the dragon’s belly unharmed, so Saint Margaret had the power to bring forth healthy infants and spare the lives of their mothers.”

I found it very poignant: medieval women, in their time of great pain and danger, kissed this painted image and sent up prayers to St Margaret to save them and their babies. I began to imagine these women, especially those giving birth for the first time.

And the plot began to take shape, the story of the mother and the daughter, and the story of a sacred book, believed to have the power of life and death.

Of course I realised that a great number of women did die in labour, and the babies who were born into these situations would be raised by others. More of the plot began to take shape in front of me, like a beautiful picture being drawn before my eyes.

So this was where the story began, and it is also where it ends. The book of St Margaret is passed on to another mother; to read, to bless and to make intercession for those in pain and grave danger.

The Passio of St Margaret ends with this entreaty to the unborn child.

“Come forth. If you are male or female, living or dead, come forth for Christ summons you, in the name of the Father, and the Son, and the Holy Spirit, amen.”

(translated by Prof. John Lowden)

Now that my book has been brought into the world, I hope its readers will see something of the courage and strength of medieval women, and all those women living now, around the world, giving birth with little or no medical help. And the powerful hope and desire they have for their children to come forth whole and unharmed.

Kate Innes