|

| The Thinker Monkey from the Breviary of Mary of Savoy, c. 1430 Lombardy, Chambery Bibliotheque Municipal, MS 4 fol. 319r Notice his belt, to which a chain would have been attached. |

I had an encounter in South Africa which made a deep impression on me.

It was with a gibbon.

And it was in a zoo.

One is not meant to go to Africa to meet southern asiatic apes in captivity. But that is what happened and it has made me think carefully about the parts of human society that we project on to apes and monkeys, and the schizophrenic attitude we have towards them.

The children wanted to go to ‘Monkey Town’ link , and, to be honest, I did too. Because I enjoy seeing the beauty and variety of animals across the world, I do put aside my concerns and scruples about caged animals and occasionally visit zoos. It is something that causes me pleasure and embarrassment in almost equal measure. And if it is a place I have not visited before, I approach with trepidation.

In this case my fears were, for the most part, unfounded. The enclosures were large and well designed, and it was the walkway for the humans that was caged, allowing the monkeys plenty of space to display their incredible acrobatic abilities. However, what made the visit extraordinary was the desire of many monkeys to interact with the human visitors. One spider monkey played push-me pull-you with my son and a twig. The marmosets raced us to and fro.

But when we came to the gibbon, things were quite different. There were several gibbons in a large enclosure, and when I came to the fence a few moments behind the rest of my family, an older female gibbon was already holding my daughter’s hand.

She held each of our hands in turn. This went on for some time. Then she turned around and hung, with her back to us, against the wire fence. She wanted her back scratched. All this time she did not make a sound; just gazed at us, calm and self possessed, with her intense melancholy eyes. We stayed with her until the zoo closed.

The gibbon is one of the ‘lesser’ apes, due to its smaller size than gorilla, chimp and orang-utan. It is tailless, but still is the fastest and most agile tree-dwelling mammal, due to the extraordinary length of its arms and the clever ball and socket joint in its wrist. Gibbons have been observed to mate for life.

Monkey Town is home to many apes and monkeys who have been rescued from neglect or inappropriate environments. There was one who was a recovering alcoholic, as his previous owner had given him beer to drink every day. Although I do not know this female gibbon’s history, it seems likely that she was used to human contact and company, and although there were plenty of other gibbons to interact with and she had obviously born several babies, she sought out human interaction.

In the Medieval period in Europe, apes and monkeys were popular pets for the rich. They became an exotic status symbol, and it is quite common to see examples of fettered monkeys in the margins of medieval manuscripts. But the ape and the monkey were also symbolic of degradation, sin and the devil in the Medieval world view. They were ‘man unbounded by constraint’, and as such, a symbol of those who give into their animal cravings, most commonly lust and greed. And they were a very useful satirical tool for the artist. See Apes in Medieval Art

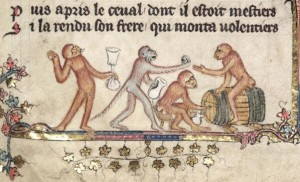

|

| Monkeys drinking – from Roman d’Alexandre – Tournai early 14th century |

By contrast, in China where the gibbon is a native, they featured prominently in ancient Taoist poetry, were known as the ‘gentlemen of the forests’ and considered noble. Gibbons were believed to be able to live for hundreds of years and to transform themselves into humans. Their incredibly powerful voices, calling across the Yangtze gorges, came to represent the sadness and melancholy of travellers far from their homes. But this respectful view did not stop people from destroying the thing they admired in an attempt to own its beautiful qualities.

“The popularity of captive gibbons being kept as pets appears to go as far back as written history . . . The traditional method to catch a live gibbon always consisted in looking for a female carrying an infant, then killing the mother with an arrow or a poisoned dart from a blow-pipe and taking the infant still clinging to her when she has fallen dead onto the ground. Humans often became deeply attached to their pet gibbons. When a king of the Chou dynasty (i.e. Chuang-wang, 613-591 B.C.) had lost his gibbon, he had an entire forest laid waste in order to find him.”

See this informative blog from Thomas Geissmann : gibbons in chinese art and poetry

|

| Two Gibbons in an Oak Tree by Yi Yuanji Song dynasty |

Neither of these extreme views are particularly helpful for the apes and monkeys who have to negotiate the human wasteland or human jungle. Both are merely a shadow, a reflection of us – that we project onto these intelligent animals. We are fascinated by the degree to which they are like us, and not like us – as we are with our own children. Turning wild primates into pets seems to be part of a desire to make them even more like us.

Will that help them in this human dominated age? Will it harm them?

Having met a gibbon, who was obviously affected by past human contact, I see the contradictions in my own feelings. It was an extraordinarily moving experience to be trusted by a gibbon. It made me hungry for more interaction. But that gibbon had been forced into our humanised environment. Forced to live in a house and a zoo, and if nothing is done, that may be the only environment in which gibbons do survive.

The IUCN Species Survival Commission has declared that 2015 is the Year of the Gibbon. Almost all of the gibbon species are endangered due to habitat loss (99% of habitat in China already gone), hunting and illegal trade. Mother gibbons are hunted and killed, just as they were thousands of years ago, in order to acquire the babies for the pet market. Often, both mother and baby die.

In Britain, one is allowed to own primates as pets. One can buy a baby monkey on the internet, with little or no regulation. In 2014, the government decided not to ban the owning of monkeys as pets, claiming this law would be ‘draconian’. They decided that no legislation should be approved until more was known about the situation. Here is part of the response from conservation organisations.

Philip Mansbridge from Care for the Wild said: “The report says that there are a lot of unknowns: we don’t know how many primates are kept as pets, we don’t know how well they are kept, we don’t know if existing legislation is working. But deep down, we do know one thing: that monkeys, chimpanzees and other primates ultimately are not objects for us to own. And that information alone should be enough to settle this debate once and for all.”

The Guardian 10 6 14

Let us work towards a world where primates do not need to be rescued,

because they are swinging through their forests,

calling across the deep ravines

to those of their own kind –

grooming and holding each other –

clinging to their own mothers

and living out their own lives.

Kate Innes