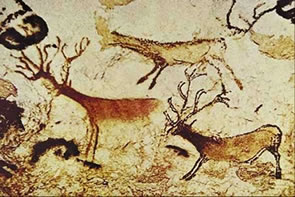

Reindeer from Lascaux Cave, Dordogne, France

To enter a cave is to leave this world, with its rain, wind, cold or heat, its light and its far horizons. Inside the cave, imagination may become reality. The strange inner space allows the mind to explore the gap between what we see and hear, and what we feel or sense.

Four years ago I visited the cave system of Isturitz and Oxocelhaya in the French Pyrenees, and the beauty of the cave formations left me speechless. Unfortunately it did not have this effect on my three young children, who spent most of the tour saying that they were bored and wondering how soon they could go to the shop.

Grotte Isturitz, France

I doubt that children in the Ice Age would have been so nonchalant. 17,000 years ago, the people of southern France faced a harsh environment. They shared the land with many arctic species and a cave such as this would have provided welcome shelter. With only flame-light to see by, the deep parts of the cave would have been mesmerising and frightening. The guide told us it was likely that Paleolithic people used the thin sheets of rock as percussive instruments, hitting them with sticks or bones. They played a recording. It was strange and echoing, like a hybrid of organ and tympanum.

The paintings and engravings in the cave were not as elaborate as those found at Lascaux or Altamira, but the carved antler and bone tools were beautiful. Spear throwers used the stored energy of a lever to increase the speed and power of the throw, much as ball throwers used by dog walkers do today. They were carved with detailed images of animals.

Hyena spear thrower found in Abri de la Madeleine, France

The visit made me think about the relationship between the artist and the hunter. Not only did the hunters carry accurate representations of these animals on their weapons and tools, they also brought them into the caves, into the sterile, inert dark, where they brought the animals to life with ochre and torchlight, and the sound of bone on stone.

Reindeer Hunt

Nostrils flaring with an unease borne on the air,

the buck stands in front of its herd.

It will be rendered on the stone in red lines.

The curves of the cave will be its haunches,

the striations, its tendons.

A man lies on the part-frozen ground, stalking.

He watches the twitch of skin

across bellies taut with young.

He knows how the entrails will spill,

how the flint will part muscle from bone.

Thin tufts of grass are lined with frost,

and the deer stand out against the snow-bearing sky.

He already feels the grit of the iron oxide

on his fingers, tracing the line of the back

up the bristled neck to the antler’s point.

Drawing back his antler spear thrower,

the hunter rises and shoots.

He hears the spear strike and stay.

Hooves strike the ground, hearts drumming,

and the herd is blown like smoke.

After twenty paces the buck’s legs collapse.

It is on its knees, head back.

In its clouds of breath, droplets of blood hang suspended.

This will be rendered in red pigment

shot through a reed from the painter’s mouth

onto limestone air.

The hunter comes with his flint knife,

but the image is complete.

The painter’s mind is empty.

With his hammer he will strike the curtain of stone.

He will live; the deer will live.

Kate Innes