Creative Writing for the New Year

Are you thinking about spilling some ink this year? Or maybe you prefer the keyboard?

Either way - writing can be a great way to get things off your chest. Expression is very important for mental health. For some people that happens through music making, acting, sport, home decoration, conversation, DIY, craft or art - but for some of us - writing is the best way to get those thoughts and feelings out.

As a follow up to my conversation with Clare Ashford on Radio Shropshire on 3/1/24 at approx 11:20 get (link) I have compiled this list of creative writing courses and opportunities in Shropshire or Online over the next few months. There's lots to choose from and all the instructors are writers I know and trust. They will be reliable guides into the surprising and exciting realm of your creative subconscious.

I'm also thinking of offering a writing course later in the year - once I've finished editing my next book. If you'd like to hear about that and other opportunities/events - do sign up to my email newsletter. I only send out emails about 6 times per year, and promise not to clog your inbox with junk!

So scan the opportunities below and see which appeals. I began my journey into professional writing with a course at the Gateway Arts Centre in Shrewsbury. Maybe one of these opportunities will turn into a lifelong joy for you, as it did for me!

Online 10 week Creative Writing class taught by the excellent Janie Mitchell through Adult Learning Wales on Wednesday mornings. Free if you live in Wales - £162.50 fee if not. https://www.adultlearning.wales/en/course/51957?fbclid=IwAR2hdW_zs4d51DhsycZWKkEBGiy5lKVF-bGaBTh905N7lJTFFmr_9cw4j5g

Jean Atkin runs two creative writing courses per year, called 'The Poetry Wire'. The first one is fully booked but get in there early for the second one of 2024. She's brill! https://jeanatkin.com/book-onto-a-workshop/?fbclid=IwAR0ffTHjMXTCdJeKCJwczhvSjUngeNvSQssGYdL9OmBwAKBH_USyl3ZchJk

The lovely and insightful Pat Edwards runs 'Touch Paper' writing workshops every month at the Poetry Pharmacy in Bishops Castle (see below) Sun 28th Jan 12.30-2.30 at the Poetry Pharmacy £10 inc coffee and cake plus a resource pack to take away.

As many will know, The Poetry Pharmacy in Bishop's Castle is a creative writing hub for Shropshire and the Borders, as well as being a beautiful shop and delicious literary café. Founder Deb Alma says: we hosted 34 writing and/ or arts for health workshops here in 2023, including 'Touch Paper' plus 15 online sessions, and in the next couple of weeks we'll be starting to put together a programme for next year. They tend to get going from February. Best thing is to sign up to our newsletter from our website http://www.poetrypharmacy.co.uk

Speaking of hubs - Shrewsbury Library is a great one! There you will find Bethany Rivers, who specialises in writing for mental and spiritual wellbeing through Mindful Words. She says: I'm running a creative writing course on Thursday mornings, starting 4th Jan, 10am - 12.30 for 12 weeks, online, £215. And I'm doing a 6 week writing for wellbeing course at Shrewsbury Library, Friday afternoons, 2-4pm, starting 26th Jan. £95. Contact Bethany at https://www.bethanyrivers.com to sign up for either the in person or online courses.

Hope you enjoy surprising yourself with what you create. I certainly did!

Confessions of a Micro Publisher: My most costly mistake

Confessions of a Micro Publisher: My most costly mistake

There are some mistakes in life that cause brief embarrassment. Some cause us momentary inconvenience. My biggest professional mistake (so far) was longer-lasting than that.

It’s only now that I feel able to admit to this mistake, now that the hours and hours and hours it took to rectify have come to an end. More than two years later.

I’m an Indie writer, and therefore also a publisher. Sometimes this secondary aspect of my job trips me up. I hope that writing about my mistake might save myself and others from the same pitfall. Maybe we’ll fall into a different pit – after all there are so many – but not this one!

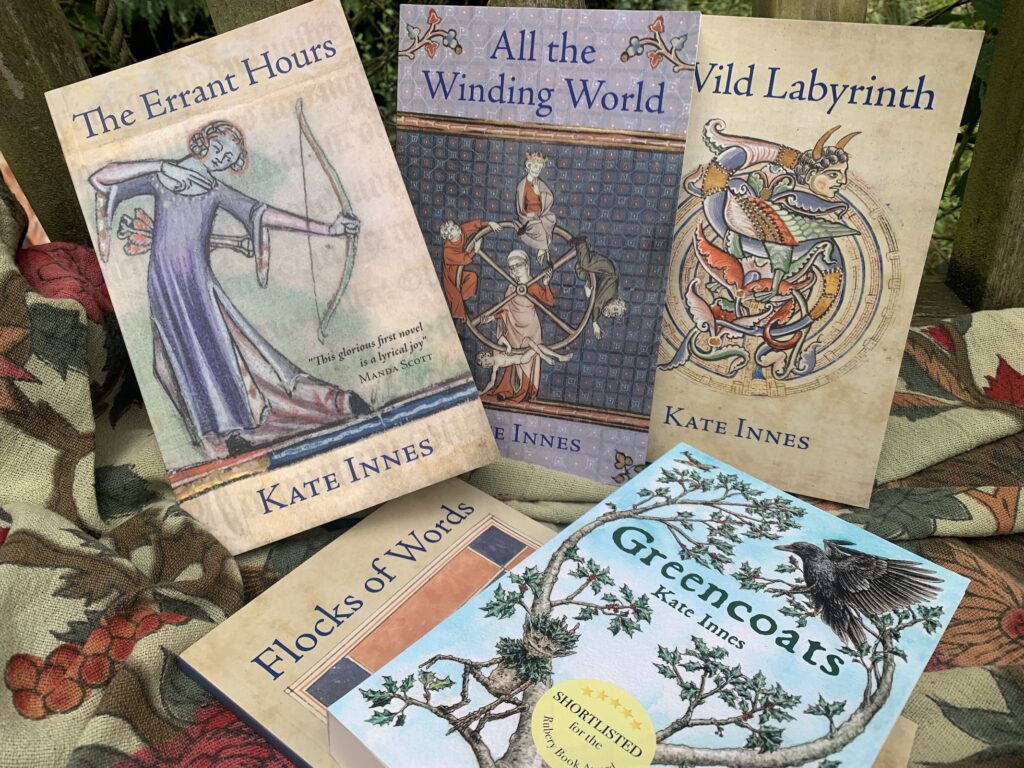

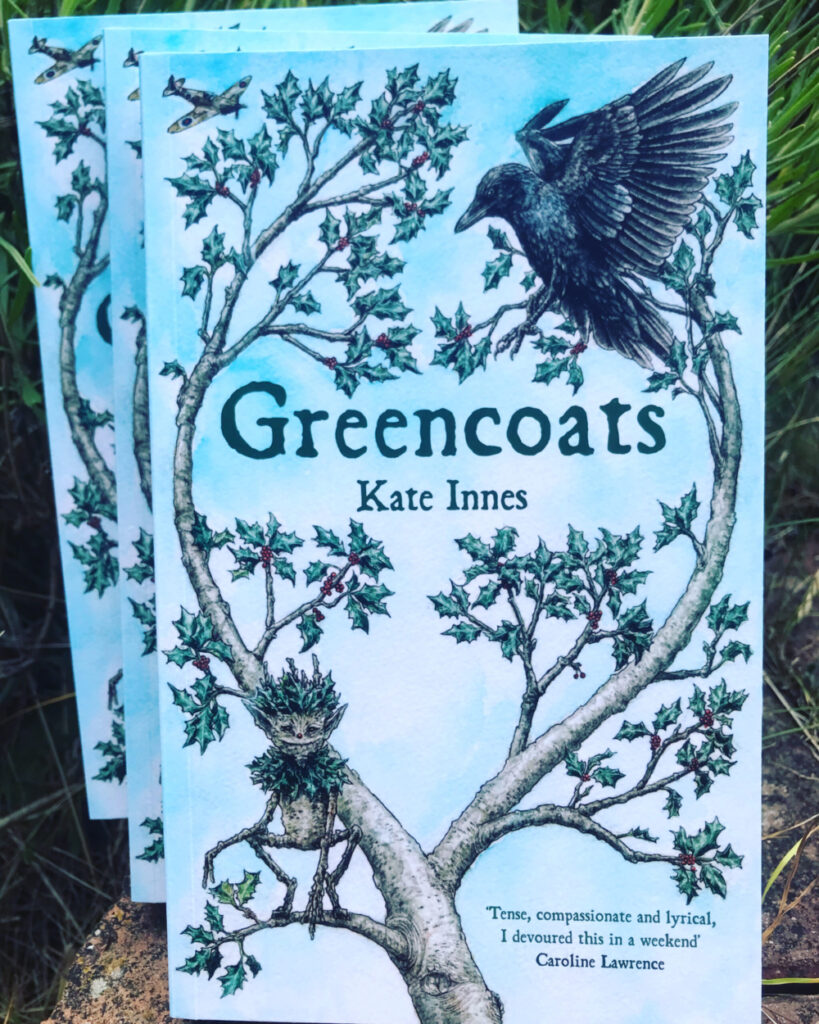

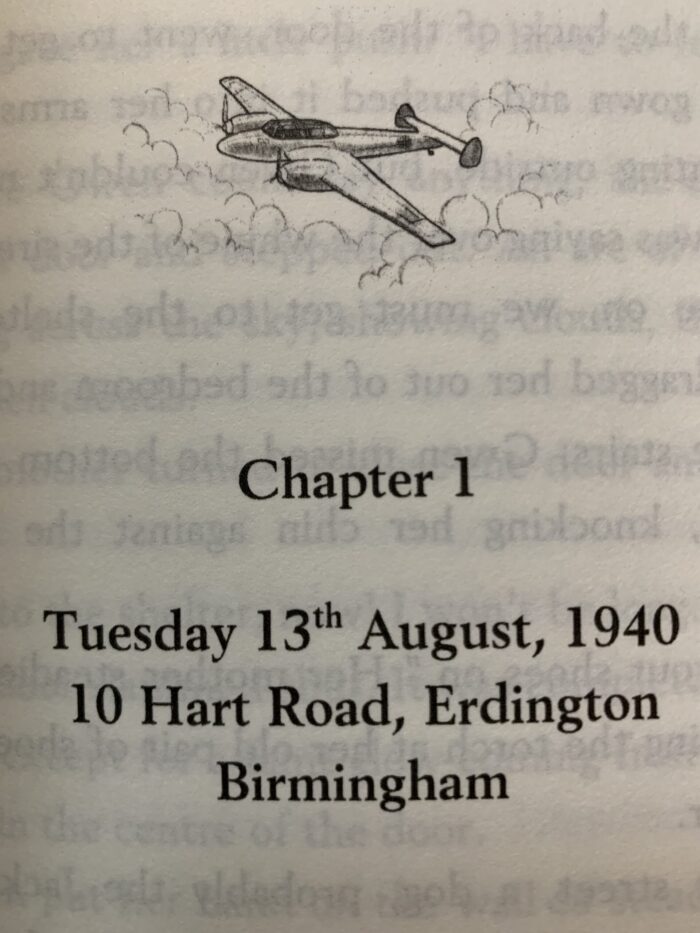

It was 2021 and I was finishing my 4th book – the first for children – entitled Greencoats. I had taken care to choose a font that’s easy to read, for those readers (like all my own children) who have a degree of dyslexia. I’d found an excellent illustrator, Anna Streetly, to bring the historical fantasy world to life and beautify the text with some motifs. I edited it over and over so that the sentences would flow. It was ready to go to the printer – or so I thought.

I have an old computer. Seriously old in computer years. The software is also old. I tried new-fangled things like Scrivener – said to be excellent for preparing manuscripts – but I couldn’t get on with it. I like my old, familiar ways. I trained as an archaeologist after all. I know where I am with ancient things.

But computers develop glitches the older they get, just like people do. They run out of memory and energy. They become intransigent about certain demands and expectations. They end up saying ‘No’ more often than not. And it is particularly common for one of these glitches to occur when you need to do something in a hurry.

I don’t even remember why I was under pressure on that day. It was April of 2021, Covid was still in the air, I had 3 teenagers at home and I was planning on publishing two books before Christmas. I had to get my skates on. But there was some particular reason that the manuscript had to be approved on that day, and it was probably because I’d already had to stop one print run half-way through to change the uneven type setting. That was expensive. If I didn’t get this version to them, they wouldn’t be able to deliver before the (small, socially-distanced) launch event in May. All my plans would fall apart.

I had noticed that sometimes when I saved the book file as a pdf, the page numbers disappeared. Then I had to perform some magic spell with scroll down menus to get them back. Something about the margins, the footer, the page layout. As I went through the numerous checks, I was sure they were showing up where they ought to be – doing their job of telling the reader where they were and how far they had to go. I pressed ‘Send’, and later that day I pressed ‘Approved for Print’.

Fast forward two weeks to the moment I open the first box of books.

No page numbers.

I almost faint. The printer must have done something wrong and not printed the base of the page. But it’ll be the printer who has to fix it. And fix it quick! I run to my desktop and reload the proof that I approved.

No page numbers. It’s my fault not the printer’s.

I stand still for a long time feeling sick. About £1000 of investment, and these books are useless. I want to cry. I want to burn them. I want to give up.

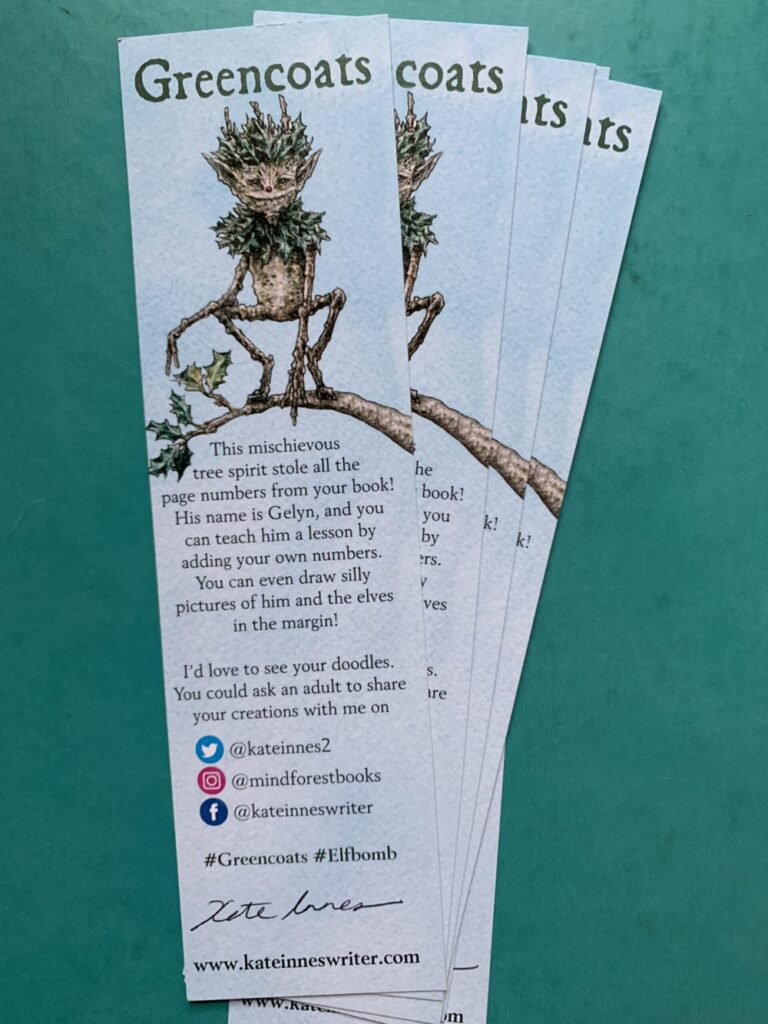

Instead, after a few deep breaths and lots of swearing, I conclude I’ll have to live with it. I don’t have the money for a reprint. Everything else about the books is perfect. Serves me right for writing a book that includes Forest Spirits and Elves. Of course they would make mischief. What was I thinking??

And why do we have to have page numbers anyway???

I decide to visit one of my best friends. We laugh. Well she does, and I pretend. Then she gives me the first solution. A genius way of looking disaster in the face and smiling anyway.

Engage your audience.

Turn a weakness into a strength.

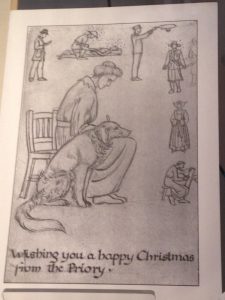

Carrie Bennett was excellent at PR and Marketing. It was one of the jobs she did brilliantly. She died last year, on this day, and her loss has been hard to bear for all those who knew her. She was a very kind, unique, generous and gifted woman.

The addition of the bookmarks made everything okay. At the Book Launch, I was able to make light of it and see the empty whiteness at the bottom of the pages as freeing, expressive, doodle space. (To those of you who never write in your books and never dog-ear pages either – I apologise).

I also ordered a small emergency supply of print-on-demand books with the page numbers in their proper place to give to bookshops. Phew. But I quickly ran out of bookmarks and numbered copies.

I also realised that it was impractical for schools to use books without page numbers, and I dearly hoped lots of schools would use Greencoats as part of their WW2 curriculum.

I needed another solution.

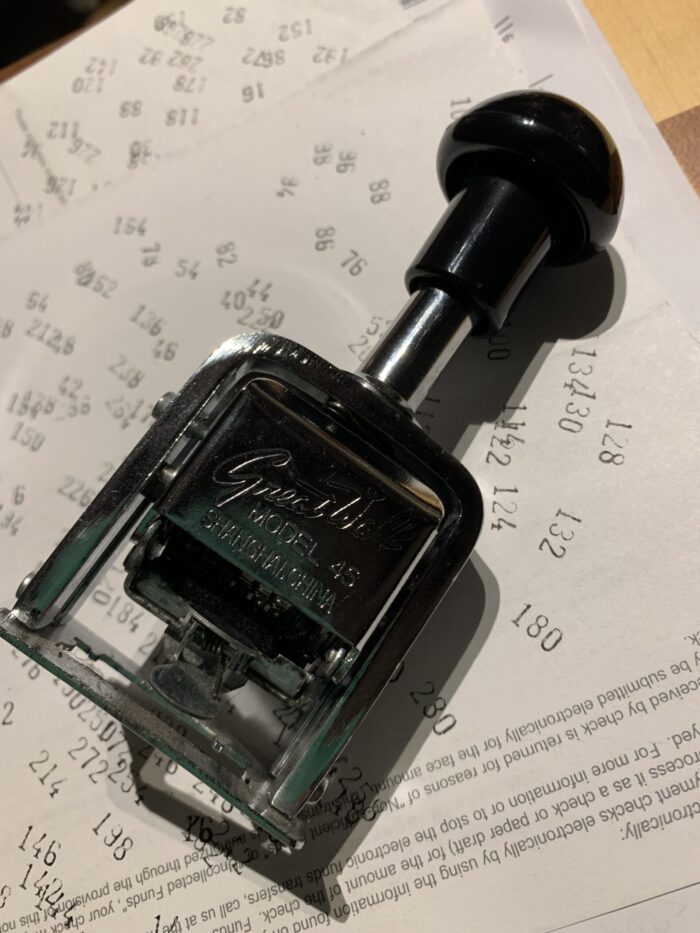

And that’s where my Great Wall Model 46 Mechanical Numbering Stamp from Shanghai came into the story.

Luckily I enjoy watching tennis, rugby, athletics, and other Olympic/Commonwealth sports. I sat in front of the tv with a wooden chess board on my lap, a cushion at my back, and stamped every other page with an odd number. I stamped the even number onto a piece of paper. It was too complicated to move the book to and fro to get numbers on each page, and the ink would have smeared.

I made lots of little mistakes, like printing the numbers upside down, or missing a number because someone was about to score a try or win the gold medal.

I still have a few of these ‘Seconds’ in a Box of Shame near my desk.

But after a while I got better at it and managed to ink the pad just enough, get the numbers in the right place on the page, and the clever thing would click over – all the way to page 285.

A number seared into my brain.

On the positive side, the stamped numbers have a lovely vintage look, which is appropriate for a book set in 1940. I estimate that I numbered around 170 books. That’s approximately 48,450 times I pressed down that mechanical numberer. It’s still in perfect working order. I’m impressed. Great manufacturing.

But am I in perfect working order?

No. I never will be. I’ll always make mistakes.

But now I have a new mantra. A motto I whisper to myself whenever I’m feeling stressed about getting something done.

DON’T RUSH

I have decided that this is a key piece of wisdom that will help me in all kinds of situations, not just writing and publishing.

DON’T RUSH - with my kids, family, walks in the woods, creativity, friends, teaching, driving, cleaning, listening, and enjoying life.

DON’T RUSH

And also

THERE’S ALWAYS AN ALTERNATIVE TO WHAT YOU THOUGHT YOU WANTED – AND SOMETIMES IT’S ACTUALLY BETTER THAN THE ORIGINAL

And perhaps

IT’S ALL ABOUT PERCEPTION. PERHAPS ONE DAY THE SECONDS OF GREENCOATS WILL ACTUALLY BE WORTH SOMETHING???

And certainly

COMPUTER SOFTWARE DOES NOT IMPROVE WITH AGE. KEEP IT UPDATED.

And finally

THE ADVICE OF WISE, KIND FRIENDS IS ALWAYS WORTH FOLLOWING, AND TIME SPENT WITH THEM IS PRECIOUS.

Last week I finished stamping the last unnumbered book. The numberer has fallen silent.

I’m just getting ready to order a reprint.

Wish me luck!!

In memory of Carrie Bennett – who made everything better.

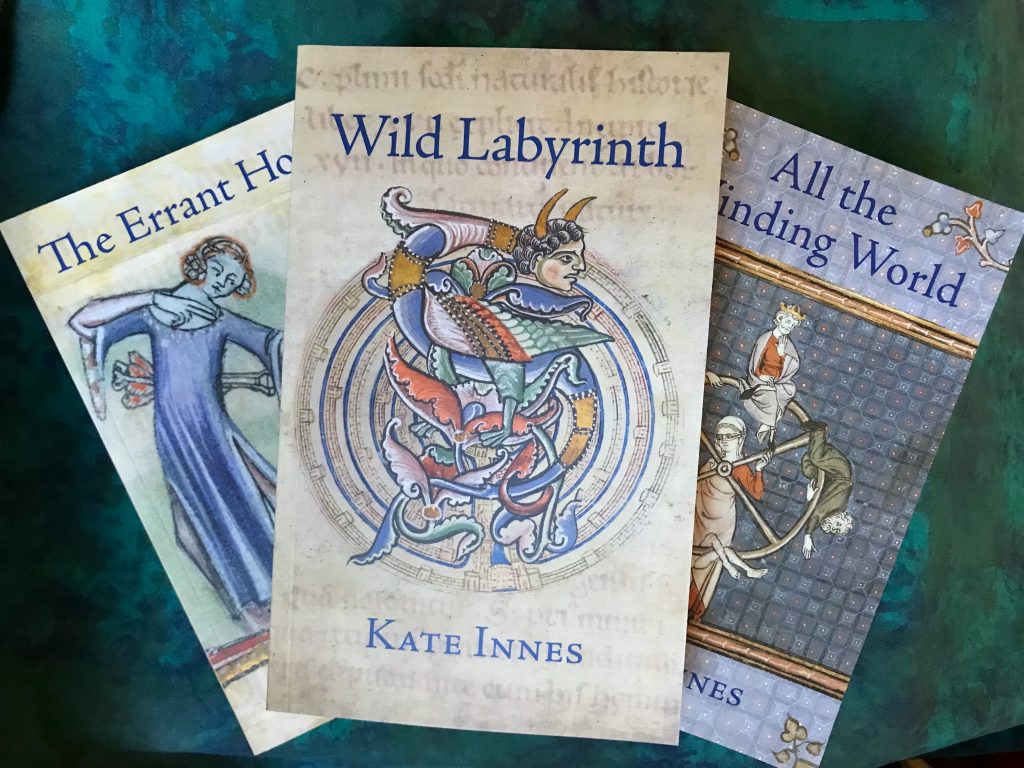

Wild Labyrinth – Review from Dr Anne E Bailey

I'm very grateful to Dr Anne E Bailey, Oxford University Medievalist and expert in medieval pilgrimage, for reading and reviewing 'Wild Labyrinth'. I'm also extremely relieved that she considered it historically accurate as well as entertaining!

Wild Labyrinth - Kate Innes

Everyone is rushing to make use of the new shrine. The monks are lining up pilgrims, standing waiting with their quills already dipped in the ink to record the new miracles. Yesterday, a blind girl was healed, but Thomas was only warming up. Today the Bishop expects a resurrection (p. 103)

As a medievalist and pilgrimage researcher, it would have been difficult not to love Wild Labyrinth.

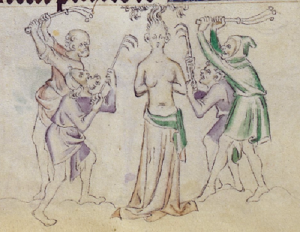

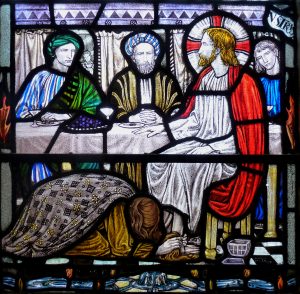

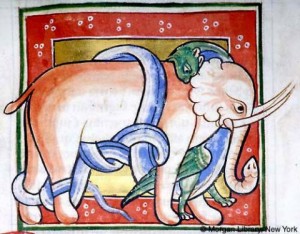

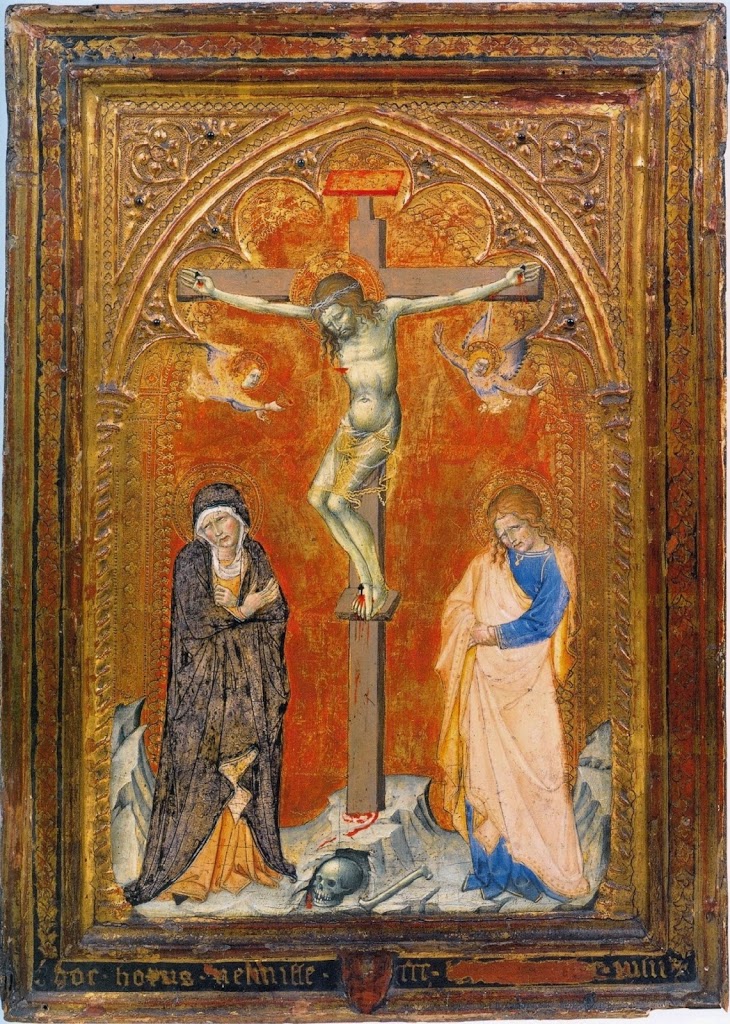

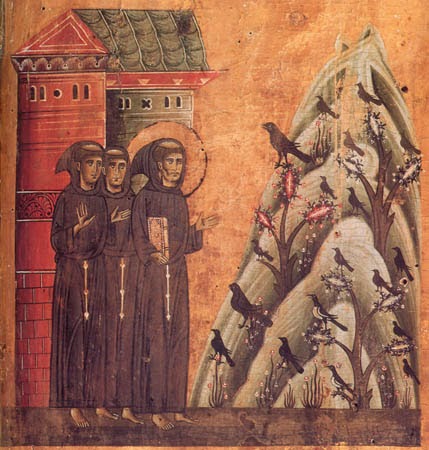

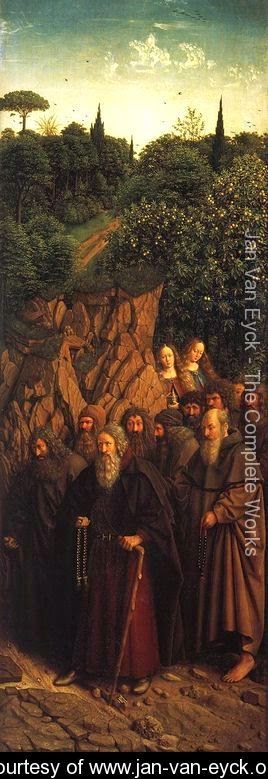

Set in the years 1306 and 1307, the story follows the peripatetic adventures of Lady Illesa Burnel, her daughter Joyce, and a fluctuating cast of miscellaneous travellers. Readers are taken on a journey to a number of well-known pilgrimage shrines including Hereford Cathedral where the recently deceased Thomas Cantilupe is attracting miracles and pilgrims, and the shrine of Our Lady of Rocamadour in France with its famous miracle-working image. On the way, we’re introduced to a variety of fascinating and intriguing characters. Among them are the villainous Reginald the Liar, the misunderstood joculator Ramón, and the enigmatic creator of the Hereford Mappa Mundi, Richard Orosius.

As Illesa and Joyce journey from London to the Midlands, and then through France to Rocamadour and back again, the medieval realm is brought vividly and convincingly to life. We get a glimpse of the world of itinerant court entertainers, we’re taken inside Westminster Hall to see the mass dubbing of knights ahead of Edward I’s Scottish campaign, and we witness the arrests of the Knights Templar in France instigated by Philip IV.

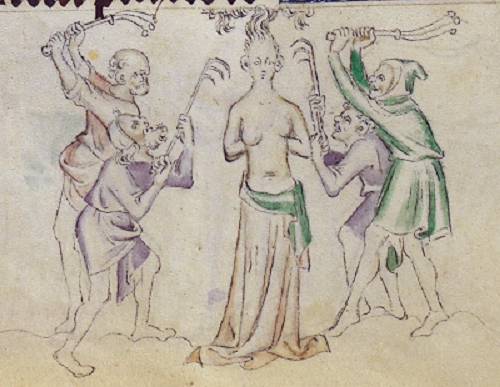

More disturbingly, we’re also shown a darker side of medieval travel when mother and daughter suffer a violent attack at the hands of a would-be rapist. However, it is this terrifying ordeal which sets the two women on the road to Rocamadour, one seeking redemption and the other a miraculous cure. On their journey they meet a variety of other pilgrims, all with their own motivations for travel. The disquieting way in which fellow travellers come and go hints that there are many twists and turns in life’s labyrinth and the goal sought is rarely close at hand.

Wild Labyrinth is meticulously researched. As well as being knowledgeable about her historical period, the author is well-versed in medical plant and herbal lore which helps to situate the story in an appealing, but culturally distant, past. With its well-drawn characters, its nicely paced narrative, its compelling storyline, and its beguiling medieval setting, this is a deeply immersive tale of travel and adventure which stays with the reader long after the journey to the final page is completed.

Dr Anne E Bailey

University of Oxford

@AnneEBailey1

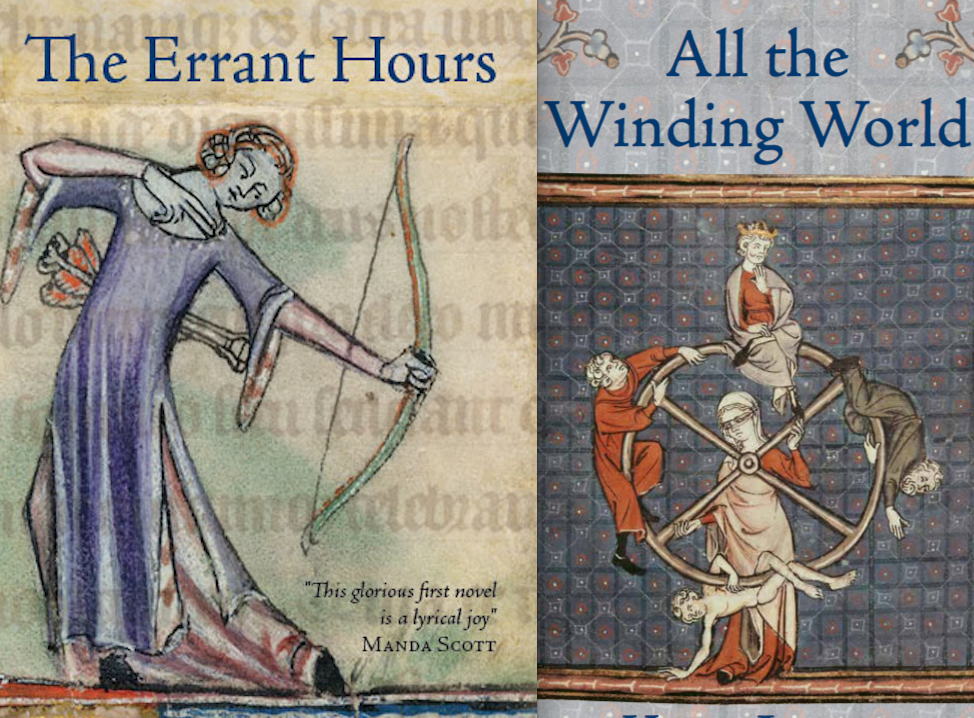

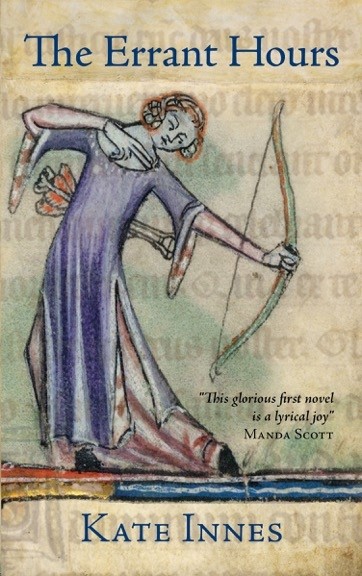

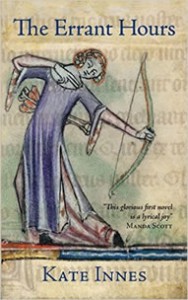

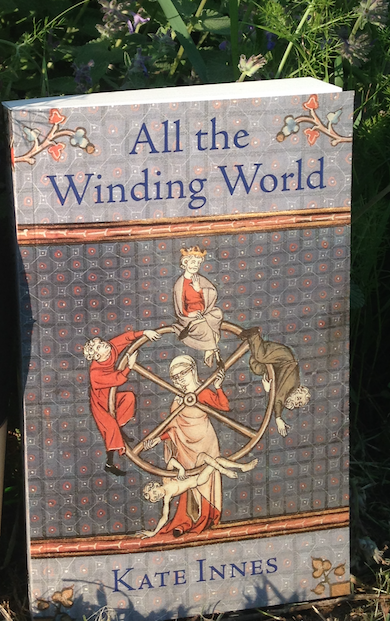

Wild Labyrinth is Book Three of 'The Arrowsmith Trilogy'. If you'd like to read these medieval literary adventures (The Errant Hours - Book One and All the Winding World - Book Two) they are all available from my Website Shop - Amazon - Bookshop.org - and Shropshire book shops.

‘Wild Labyrinth’ – review from Vuyelwa Carlin

I am very grateful to my friend, Vuyelwa Carlin, for reading and reviewing 'Wild Labyrinth' with such insight and commitment. Vu and I have been members of the Borders Poetry Writing Group for several years, and I admire her skill as a poet and value her opinion very much.

'Wild Labyrinth' by Kate Innes

This is the third in Kate Innes’ Arrowsmith historical novel trilogy, set in the late 13th / early 14th century. As always, the historical background is very impressive; and as should be with a trilogy, this last book is the best. All three are very good; but Wild Labyrinth is riveting from page one. Time has passed between the second book, All the Winding World, and this one: Illesa has suffered a miscarriage, losing a daughter; also, the reader gradually realises, she and her husband Richard are at odds. Chapter one opens (after an intriguing and atmospheric Prologue) with their son Christopher being sworn in as a knight for an unpopular war (it is 1306, near the end of Edward the First’s reign) in a packed, noisy Westminster Abbey; the atmosphere is anxious, sorrowful and unnerving, setting the scene for much of the book. This disquiet is unsettling, but not off-putting – on the contrary, it enriches the book. The book’s characters – not least Illesa and her family – are complex, faulty people; very realistic. They are mostly sympathetic and attractive, with all their imperfections; but there are two at least who are highly ambiguous – full of wit, a charm which may or may not be manipulative, and an uneasy oddness; part of the writer’s skill is that the reader is kept guessing for some time as to their real natures: are they to be trusted?

The narrative, very adventurous, often tense, sometimes horrifying, goes along at a good pace right from the start; as I said, the book is a page-turner. The story is of journeys made – in more senses than one: by Illesa, her family and their manservant William, and by the maker of the long-famous and treasured Mappa Mundi, who joins them as an eager but highly temperamental guide. This last is a beautifully realised character; the few facts known about him have been combined with a very creative imagination to build up a moving portrait. Richard Oriosus, a scholar and artist of genius, is difficult, obsessive, puzzling and contentious, a man of suffering and regrets; in the end, he is deeply sympathetic. It is he who speaks the highly evocative Prologue, describing the making of the map, the first of several fascinating accounts, encompassing as they do his brilliance, his almost fixated dedication to his work, and of course the state of knowledge of the world: "… I drew the centre of the world – Jerusalem’s wall encompassing the dome of the Holy Sepulchre…" To him, the map is an artistic endeavour to the glory of God – bound up too with his own past; a profound sorrow is hinted at. To others, such as his Bishop, it is mainly a means of attracting pilgrims hoping for miracles, and their donations. Here, as we realise – he doesn’t mention her name – he first meets, and remembers, Illesa.

The book immerses the reader in the past of over seven hundred years ago: its strangeness and also its familiarities. Kate Innes knows her subject extremely well; she has imagined herself, with vivid accuracy, into ways of thinking and beliefs that in some ways are alien to us. But the characters are completely believable. We human beings have changed so completely in some ways; and so little in others. This is part of the fascination of history. What strikes me particularly (as with the other two books) is the way in which people’s lives are soaked through with religious belief. Everything that happens is explained, one way or another, in accordance with a faith that is taken as read; an engagement with a God of sometimes disturbing and incomprehensible ways, and complex angers. What strikes me is that this is not described from above, as it were – that is, from a position of implied superiority; the writer understands and respects – implicitly sifting obvious superstitions from possible truths – the absolute conviction of those days that God was intimately involved with human affairs. This encouragement to think ourselves into a different time does not always preclude dramatic irony: for example, there is a painfully moving account of what is clearly bipolar disorder: the reader knows this at once, but for the sufferer it is an affliction imposed upon him by God, which (however imperfectly he understands the reason) he must endure.

It is also brought home to us how shockingly dangerous, especially for women – and how long, cumbersome and uncomfortable – travel was in those days.

This is a many-layered book; the story is a dense mesh, wide-ranging and excellently plotted, full of real people about whom one is curious, and detailed information about their everyday lives, assumptions and knowledge: we inhabit the peculiar atmosphere of a distant past. The author’s wide knowledge does not intrude, however (I have read novels where the research gets in the way) but is bound in as a whole with the story. No spoilers, but I very much liked the endings: there are two of these, as characters part ways.

Vuyelwa Carlin

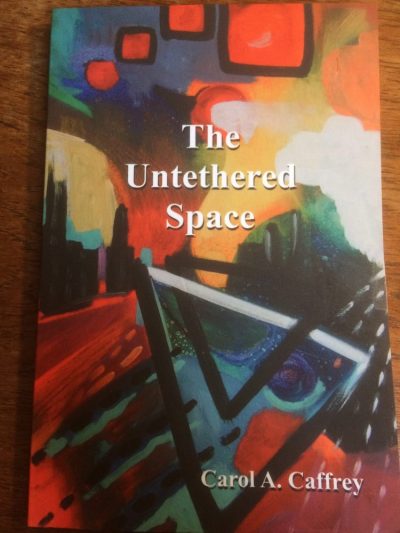

Review of ‘The Untethered Space’ by Carol A. Caffrey

Is it possible to find beauty and meaning in life in the aftermath of grief? How do we interact with the too present world when our inner world has fallen apart?

These questions have been explored by artists of all kinds for thousands of years – but I would argue that Carol Caffrey’s pamphlet, written during and after the deaths of all her four siblings within five years, is a beautiful, meaningful and earthy contribution to this, most human, of tasks.

The Untethered Space is a potent mix of writing: elegiac and entertaining – practical and metaphysical. It floats between the spirit and the flesh – and celebrates each. In contrast to and affirmation of the title – many of the poems explore the poet’s strong attachment and belonging to Ireland – where she was born and raised but no longer lives. That longing for a land, the missing of the family home and birth place is made more poignant by the shattering loss of those she shared it with. But there is no self-pity – rather the poet’s close observation and appreciation through deft, musical language of what life gives – the joy, the humour and the devastating significance of everything.

In ‘The Waiting Room’ Caffrey, who is also an accomplished actor, brings her understanding of timing and voice to bear in the final stanza:

“We saw what courage looked like, what grace under

pressure means. It was in that room and in your voice

when, home for the last time, you said that his words were

very hard to hear and at last allowed yourself to cry.”

An aspect of the collection that I found very significant was the political poetry – because when you make connections with suffering in yourself and those you love, you also notice it in the world and understand the grave consequences of political power-play. This is profoundly expressed in ‘Baghdad Echo’ where Caffrey deftly explores the universal outcome of violence – from the point of view of a journalist:

‘The city burns in flames, the naked prisoner in shame.

Insurgent, martyr, brother –

he remarked they bled the same.

He filed his copy in the rubble

of Dublin, Easter nineteen sixteen.”

And in between the beauty and the wide insight – there are poems that cheered me up enormously, including ‘Thoughts from the Treadmill’ in which, combining influences from the canon of history and literature, the poet cries out for salvation from the hyper-fit brigade.

“Let them take their sleek and tanned

perfection home to sterile empty fridges.

They’ll never taste of chocolate but once;

I’ll do so many times before my death.”

The collection is helpfully divided into sections described by Italian musical notation – such as Con Brio, Espressivo and Misterioso. These give the reader a sense of lift into another realm, of travelling with an intriguing and sympathetic companion. I believe readers will be glad of the time they spend in Carol Caffrey’s company – tethered briefly in her mind's space.

The Untethered Space is available from 4WORD Independent Press 4word.org – cost £5.99

Refugee Week – Creative Transformation Writing Exercise

Creative Transformation:

In this creative writing exercise we are going to be allowing ourselves to go into positive, rewarding, uplifting territory.

That doesn’t mean we deny that terrible and horrendous things are going on, and in some cases have happened to us and people and places we love.

It means that we are giving ourselves a place to go where we are in control of what happens. We can make good changes. We can meet out justice.

If we think about all the bad things happening, we feel awful if there is nothing that we can do to help make it stop. But, it is very helpful to give ourselves something in fantasy that we can’t have in reality. This helps us all to think more positively and happily about ourselves and the future.

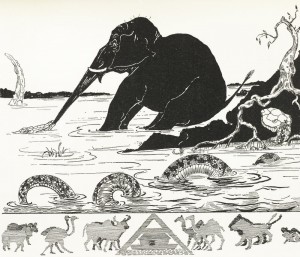

This technique has been used in fiction from the earliest myths about the Greek gods and the ancient tales in the Arabian Nights – to Roald Dahl in his stories like The Magic Finger (in which selfish people are turned into ducks) – and changing something scary into something ridiculous in JK Rowling’s book Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban.

In the sovereign territory of your imagination, you can make anything happen – you can make anything change. You can use a supernatural force – like the pagan gods or superheroes we have in popular culture today – or you can use prayer or magic.

Or you can just decide that this is how it is going to be.

One of the poems in my sequence Modern Mythic Metamorphoses – ‘In which the hunters mysteriously disappear’ changes the rules so that as soon as a hunter tries to shoot an endangered animal, that hunter transforms into the animal he was trying to kill. This then leads to an increase in animal numbers and an increase in forests and other wild places – and greater biodiversity. Through one little change many other good things result.

You can watch the video of this poetry sequence here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D1tKwDjDrbg&feature=youtu.be

So – in this creative writing exercise - don’t worry about being realistic.

Give your imagination plenty of freedom to dream and create a better world.

Write a short description – can be prose or poetry – of a transformation.

1. Think of a situation or a person that needs to be changed.

It can be political, social, or very personal. It can be someone who lives near you or on the other side of the world. It can be an object that you think should not exist in its current form. (eg. what would happen if all mobile phones turned into tulips?)

2. Name what will be changed: ______________________________________________________________

3. Name the animal, plant, thing, situation that you will change it to:

___________________________________________________________________________________________________

4. Now write about the transformation and the outcome of it – how have things changed for the better – or are there some unintended consequences of your divine intervention?

Spend about 10-15 minutes getting the basics down.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________________________________________

Sometimes a poem or piece of writing is quick and sometimes it takes a long time. Spend some more time making this work as good as you can. If you’ve enjoyed it, you can choose another situation or person who needs the creative transformation treatment.

There is no limit to what you can do – you are in charge.

If you want to share your ideas with us, that would be great! Share to the Refugee Week post on my Facebook page https://www.facebook.com/kateinneswriter/

or email [email protected]. I will respond in both cases.

If you have emailed me, I will ask if you would like to make your work public or not.

If you would rather not share at all – no worries – keep it as your powerful secret.

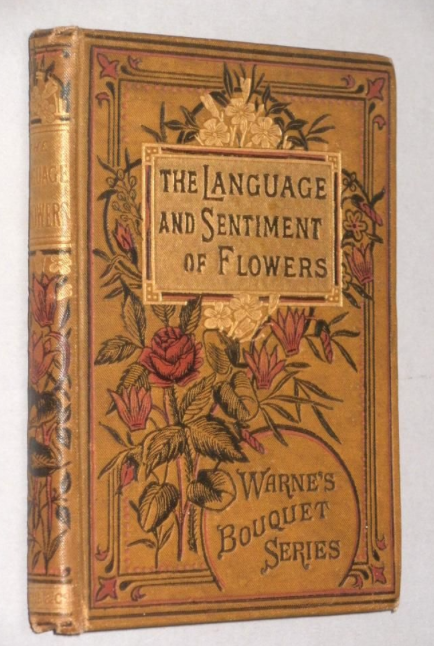

Wildflowers – folklore, literature, language

Here is the support material and the resources for my video about Wildflowers in Shropshire Folklore on the #Folk

Community Group's Facebook page and Youtube channel.

Available from 12 June, 2020 at 2:00pm BST.

Writing Exercise:

Make a virtual floral bouquet for a person you haven’t been able to see during the lockdown using Floriography. The meaning of the flowers will express how you feel about that person, your situation, their absence . . . You can write this just in the flower names arranged in a certain order – or turn it into a poem or a flash fiction piece of fewer than 200 words.

Please share your work on the #Folk facebook page – if you would like to!

Floriography:

- White rose: purity, innocence, reverence, a new beginning, a fresh start.

- Red rose: love, I love you

- Deep, dark crimson rose: mourning

- Pink rose: grace, happiness, gentleness

- Yellow rose: jealousy, infidelity

- Orange rose: desire and enthusiasm

- Lavender rose: love at first sight

- Coral rose: friendship, modesty, sympathy

In a sort of silent dialogue, flowers could be used to answer “yes” or “no” questions. A “yes” answer came in the form of flowers handed over with the right hand; if the left hand was used, the answer was “no.”

| Symbolic Meanings of Herbs, Flowers and Other Plants | |

| Abatina | Fickleness |

| Acanthus | The fine art, artifice |

| Aloe | Affection, also grief |

| Amaryllis | Pride |

| Anemone | Forsaken, sickness |

| Angelica | Inspiration |

| Apple blossom | Preference |

| Arborvitae | Unchanging friendship |

| Aster | Symbol of Love, Daintiness |

| Bachelor’s button | Single blessedness |

| Sweet Basil | Good wishes |

| Bay tree | Glory |

| Begonia | Beware, dark thoughts |

| Belledonna | Silence |

| Bittersweet | Truth |

| Black-eyed Susan | Justice |

| Bluebell | Humility, constancy |

| Borage | Bluntness, directness |

| Butterfly weed | Let me go |

| Camellia, pink | Longing For You |

| Camellia, red | You’re a Flame in My Heart |

| Camellia, white | You’re Adroable |

| Candytuft | Indifference |

| Carnation | Women, Love |

| – Red carnation | Alas for my poor heart, my heart aches |

| – White carnation | Innocence, pure love, women’s good luck gift |

| – Pink carnation | I’ll never forget you |

| – Striped | Refusal |

| – Yellow carnation | Disdain, disappointment, rejection |

| Chamomile | Patience in adversity |

| Chives | Usefulness |

| Chrysanthemum, red | I love you |

| Chrysanthemum, yellow | Slighted love |

| Chrysanthemum, white | Truth |

| Clematis | Mental beauty |

| Clematis, evergreen | Poverty |

| Clover, white | Think of me |

| Columbine | Foolishness, folly |

| Columbine, purple | Resolution |

| Columbine, red | Anxious, trembling |

| Coreopsis | Always cheerful |

| Coriander | Hidden worth/merit |

| Crab blossom | Ill nature |

| Crocus, spring | Youthful gladness |

| Cyclamen | Resignation, diffidence |

| Daffodil | Regard, Unequalled Love |

| Dahlia, single | Good taste |

| Daisy | Innocence, hope |

| Dill | Powerful against evil |

| Edelweiss | Courage, devotion |

| Fennel | Flattery |

| Fern | Sincerity, humility; also, magic and bonds of love |

| Forget-me-not | True love memories, do not forget me |

| Gardenia | Secret love |

| Geranium, oak-leaved | True friendship |

| Gladiolus | Remembrance |

| Goldenrod | Encouragement, good fortune |

| Heliotrope | Eternal love, devotion |

| Hibiscus | Delicate beauty |

| Holly | Foresight |

| Hollyhock | Ambition |

| Honeysuckle | Bonds of love |

| Hyacinth | Sport, game, play |

| – Blue Hyacinth | Constancy |

| – Purple Hyacinth | Sorrow |

| – Yellow Hyacinth | Jealousy |

| – White Hyacinth | Loveliness, prayers for someone |

| Hydrangea | Gratitude for being understood; frigidity and heartlessness |

| Hyssop | Sacrifice, cleanliness |

| Iris | A message |

| Ivy | Friendship, fidelity, marriage |

| Jasmine, white | Sweet love, amiability |

| Jasmine, yellow | Grace and elegance |

| Lady’s Slipper | Capricious beauty |

| Larkspur | Lightness, levity |

| Lavender | Distrust |

| Lemon balm | Sympathy |

| Lilac | Joy of youth |

| Lily, calla | Beauty |

| Lily, day | Chinese emblem for mother |

| Lily-of-the-valley | Sweetness, purity, pure love |

| Lotus Flower | Purity, enlightenment, self-regeneration, and rebirth |

| Magnolia | Love of nature |

| Marigold | Despair, grief, jealousy |

| Marjoram | Joy and happiness |

| Mint | Virtue |

| Morning glory | Affection |

| Myrtle | Good luck and love in a marriage |

| Nasturtium | Patriotism |

| Oak | Strength |

| Oregano | Substance |

| Pansy | Thoughts |

| Parsley | Festivity |

| Peony | Bashful, happy life |

| Pine | Humility |

| Poppy, red | Consolation |

| Rhododendron | Danger, beware |

| Rose, red | Love, I love you. |

| Rose, dark crimson | Mourning |

| Rose, pink | Happiness |

| Rose, white | I’m worthy of you |

| Rose, yellow | Jealousy, decrease of love, infidelity |

| Rosemary | Remembrance |

| Rue | Grace, clear vision |

| Sage | Wisdom, immortality |

| Salvia, blue | I think of you |

| Salvia, red | Forever mine |

| Savory | Spice, interest |

| Snapdragon | Deception, graciousness |

| Sorrel | Affection |

| Southernwood | Constancy, jest |

| Spearmint | Warmth of sentiment |

| Speedwell | Feminine fidelity |

| Sunflower, tall | Haughtiness |

| Sweet pea | Delicate pleasures |

| Sweet William | Gallantry |

| Sweet woodruff | Humility |

| Tansy | Hostile thoughts, declaring war |

| Tarragon | Lasting interest |

| Thyme | Courage, strength |

| Tulip, red | Passion, declaration of love |

| Tulip, yellow | Sunshine in your smile |

| Valerian | Readiness |

| Violet | Loyalty, devotion, faithfulness, modesty |

| Wallflower | Faithfulness in adversity |

| Willow | Sadness |

| Yarrow | Everlasting love |

| Zinnia | Thoughts of absent friends |

Extracts from the work of Shropshire writer – Mary Webb (1881-1927) – focussing on wildflowers:

“Flowers like the oxlip, with transparently thin petals, only faintly washed with colour, yet have a distinct and pervasive scent. Daisies are redolent of babyhood and whiteness. Wood anemones, lady's smock, bird's-foot trefoil and other frail flowers will permeate a room with their fresh breath. In some deep lane one is suddenly pierced to the heart by the sweetness of woodruff, inhabitant of hidden places, shining like a little lamp on a table of green leaves. It is like heliotrope and new-mown hay with something wholly individual as well. To stand still, letting cheek and heart be gently buffeted by the purity, is to be shriven.”

“Mauve has a delicate artificiality, something neither of earth nor heaven. It is like the temperament which can express in sheer artistic pleasure heights and depths which it can never touch. Whether it is sultry, as in lilac, or cool, as in lady's smocks, this mingling of fierce red and saintly blue has an elfin quality. Hence comes the eeriness of a field of autumn crocuses at twilight, when every folded flower is growing invisible, and doubtless there is a fairy curled up in each. Children look for the Little People in mauve flowers – Canterbury bells and hyacinths – and, though they never find them, they know them there. Mauve enchants the mind, lures it to open its amethyst door, and behold! nothing but emptiness and eldritch moonshine.”

Quotes from “The Spring of Joy – a little book of Healing” by Mary Webb

“And I thought, as I looked round the diary that it was as good a place as anybody could wish for asking to wed. The sun shone, slanting in, though it was off the dairy most of the day. The damp red quarries and the big brown steans made a deal of colour in the place and the yellow cream and butter and the piles of cheeses were as bright as buttercups and primmyroses. Jancis matched well with them, with her pretty yellow hair and her face all flushed at the sight of Gideon. She was like a rose in her pink gown. Outside the window, in the pink budded may tree, a thrush was singing.”

From “Precious Bane” by Mary Webb

“The sky blossomed in parterres of roses, frailer and brighter than the rose of the briar, and melted beneath them into lagoons greener and paler than the veins of a young beech leaf. The fairy hedges were so high, so flushed with beauty, the green airy waters ran so far back into mystery, that it seemed as if at any moment God might walk there as in a garden, delicate as a moth. Down by the stream Hazel found tall water plantains, triune of cup, standing above the ooze like candelabras, and small rough-leaved forget me nots eyeing their liquid reflections with complaisance.”

from “Gone to Earth” by Mary Webb

Thanks to the players of the #NationalLottery for making this possible through Arts For All funding

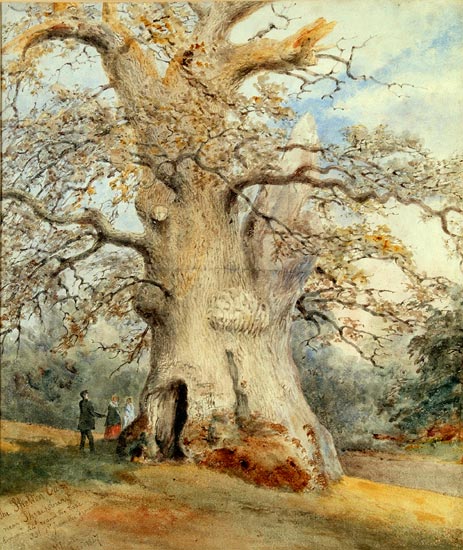

Ancient Trees – Writing prompts and Resources

Ancient Trees Resource Pack: to be used in conjunction with the video on the Facebook Folk Community Group site https://tinyurl.com/y7yps43s

The Shelton Oak by David Parkes – 19th century

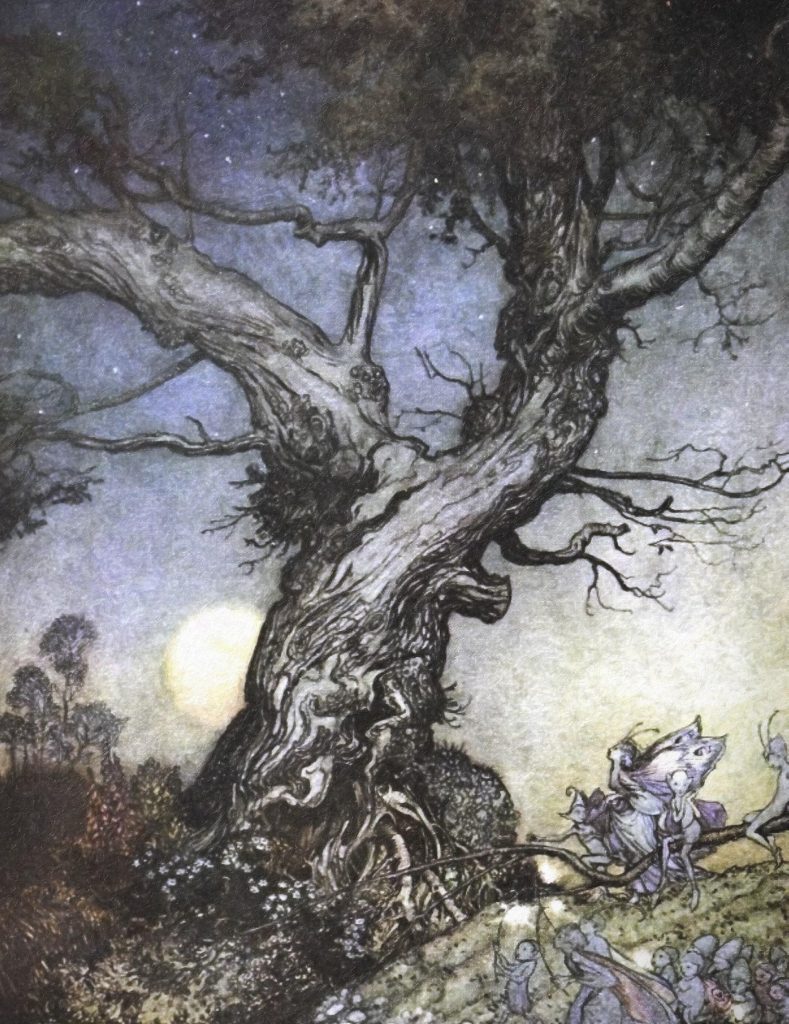

Fairy Folk by an old gnarled tree – by Arthur Rackham

Arthur Rackham, illustrator, paid very close attention to trees in his work, glorying in their detail and character.

Examples of writing about ancient oaks, other trees, and living and seeking shelter in them:

My Side of the Mountain – by Jean Craighead George

“I am on my mountain in a tree home that people have passed without ever knowing that I am here. The house is a hemlock tree six feet in diameter, and must be as old as the mountain itself. I cam upon it last summer and dug and burned it out until I made a snug cave in the tree that I now call home.

My bed is on the right as you enter, and is made of ash slats and covered with deerskin. On the left is a small fireplace about knee high. It is of clay and stones. It has a chimney that leads the smoke out through a knothole. I chipped out three other knotholes to let fresh air in. The air coming in is bitter cold. It must be zero outside, and yet I can sit here inside my tree and write with bare hands. The fire is small, too. It doesn’t take much fire to warm this tree room.”

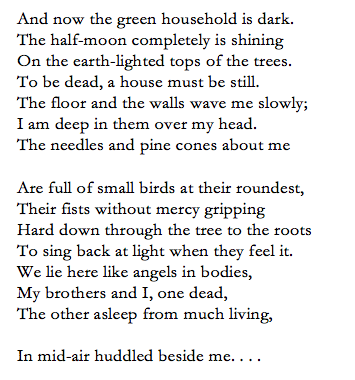

An extract from In the Tree House at Night – by James L Dickey

a beautiful, eerie poem in which the tree becomes a link between earthly life and the life beyond.

For complete poem:

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/42718/in-the-tree-house-at-night

THE OAK

by Alfred Lord Tennyson

Live thy Life,

Young and old,

Like yon oak,

Bright in spring,

Living gold;

Summer-rich

Then; and then

Autumn-changed

Soberer-hued

Gold again.

All his leaves

Fall’n at length,

Look, he stands,

Trunk and bough

Naked strength.

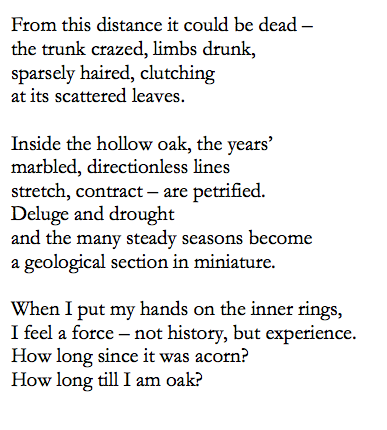

Dendrochronology (written about the Acton Round Oak)

by Kate Innes

Mary Webb – a Shropshire writer and folklorist –

From a description of Hazel Woodus in Gone to Earth

“Her passion, no less intense, was for freedom, for the wood-track, for green places where soft feet scudded and eager eyes peered out and adventurous lives were lived up in the tree-tops, down in the moss.”

From ‘The Joy of Fragrance’ in The Spring of Joy by Mary Webb 1917

‘A little wood I know has in May among its oaks and beeches many white pillars of gean trees, each with its own air round it. At long intervals a large, soft flower wanders down, vaguely honeyed, mixing its breath with the savour of sphagnum moss, and resting among the wood-sorrel. The wood-pigeons speak of love together in their deep voices, unashamed, too sensuous to be anything but pure. Among the enchanted pillars, on the carpet of pale sorrel, with a single flower cool in the hand, one is in the very throne-room of white light. A little farther on the air is musky from the crowded minarets of the horse chestnut – white marble splashed with rose – where the bumble bee drones.’

The Mary Webb Society notes that:

“Mary Webb's love and intimate knowledge of the county permeates all her work. She had an extraordinary perception of the minutiae of nature, and it is this keen observation that gives her prose its unique quality. In her introduction to Precious Bane she writes’ Shropshire is a county where the dignity of ancient things lingers long, and I have been fortunate not only in being born and brought up in its magical atmosphere, and in having many friends in farm and cottage who, by pleasant talk and reminiscence have fired the imagination, but also in having the companionship of such a mind as was my father's- a mind stored with old tales and legends that did not come from books, and rich with an abiding love for the beauty of forest and harvest field...’ “

More information about ancient trees and tree houses:

More information about the Shelton Oak, including photographs:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shelton_Oak

The Ancient Tree Forum finds the Bull Oak – a boundary tree and a shelter for a bull for years

Clip from BBC programme about the eccentric occupant of the Pitchford treehouse in the 1940’s:

https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p04bspzg

Off topic but fascinating - Pitchford Ghosts by Caroline Colthurst:

http://www.pitchfordestate.com/pitchford-ghosts

Ancient Tree Folklore Writing Prompts:

Choose any or all of these ideas to start writing about the tree as a location or as a character or its importance to you.

1. You are climbing a tree – where are you? What does it feel like? What sounds do you hear? How does it feel as you make your way up?

2. You are living in a tree house – describe that – how is it constructed and who is welcome to visit you?

3. You are living inside a hollow tree – describe your living quarters, describe how it sounds and what it feels like to live there

4. You meet the spirit of the tree – describe the spirit – how do he/she feel about your incursion into its domain? Do you have a conversation?

5. Write a fairy tale about someone who climbs a tree to escape from danger, and finds more than they expected!

6. Write a story told with the voice of the tree – perhaps the Royal Oak – or another tree that has seen incredible adventures of mice and men. Or write a story about a creatures living ‘adventurous lives’ in the treetops.

Prepared by Kate Innes – Author of ‘The Errant Hours’ and other adventures

@KateInnes2 @kateinneswriter

Digging up the Graveyard

“Once people come here, they never leave. It is the graveyard of ambition.”

When I first came to live in Shropshire, I heard this quite a lot. Now that I’ve been here nearly a quarter of a century, I see that at least some of this statement is true. Certainly I never want to leave this area and hope to live a long life amongst its hills and woods. But there is so much more to this saying than first meets the eye, or the ear. Perhaps your ambition is simply to live connected with nature amongst friendly people with relatively uncluttered roads. Or perhaps it is to live in a landscape that inspires and informs – that oozes atmosphere and ancient significance. I feel I have fulfilled both these ambitions, and even more than that - I’ve turned them into a job.

As an archaeologist and museologist, I have always enjoyed living in the past. As a writer, I particularly like to live in the medieval period, and even more particularly, I like to live in the last quarter of the thirteenth century in the Welsh Marches. Perhaps you, like me, understand that there are some locations in the world where the barrier between the present and the past is thick and strong. I’ve lived in a few of those soulless places. They usually have plenty of shopping malls. But there are other places where the boundary between present and past seems as insubstantial as gauze.

In the Marches, we can easily reach back across centuries. We sense it in the shiver down the spine in a darkened church, or the overwhelming feeling of presence when we walk alone down an ancient hollow way, or stand near one of the many veteran oak or yew trees. There is the sudden and uncanny knowledge of the many footfalls that went before us, still echoing. For me this happens particularly in medieval monuments, but I know others who feel the same about prehistoric or even Victorian locations. The Marches has plenty of history thrills for all persuasions. But for now let’s look at the late thirteenth century. Let me try to explain the attraction.

It was a time when the charismatic and peripatetic King Edward the First (later to be known as the Hammer of the Scots) travelled through this landscape repeatedly in his attempt to subdue the Welsh and appease the powerful Marcher Lords.

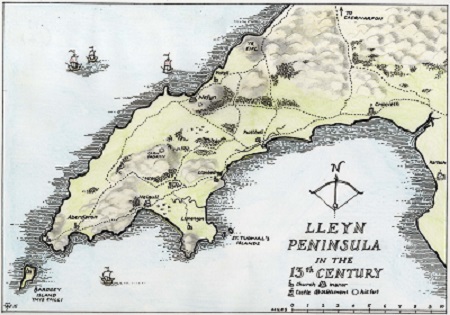

It was a time of conflict with the tenacious Welsh Princes - Llewelyn ap Gruffydd, Dafydd ap Gruffydd, Rhys ap Maredudd, and Madog ap Llewelyn, who refused to be cowed, who kept harassing the Anglo-Normans with hit and run raids and ancient guerrilla tactics. Their bands of Welsh infantry were armed with scramasax knives and spears, weapons for close quarter fighting. They harried the English interlopers who were intent on taking their land and their stock.

It was a time when the second-most powerful man in the kingdom was a Shropshire lad, Chancellor Robert Burnell, one of the greatest legislators of all time who lovingly crenellated his natal home of Acton Burnell.

‘The Graveyard of Ambition’ seems a rather negative label. However, it is not without its useful aspects. As a former archaeologist, I tend to view graveyards in a slightly more positive light than most people. I’ve spent some time excavating them, and I understand that they hold a huge amount of information - about the economy, the environment, the social hierarchy, and religious beliefs in the past. Yes, there are plenty of dead, decaying bodies, but they are very interesting dead bodies. The older they are the more interesting, in my view. And if one must see the Welsh March as a graveyard, it is certainly one of the most intriguing graveyards in Britain. The boundary that meanders between Wales and England, in eddies and oxbows of territory disputed for thousands of years, is essentially a boundary of topography, between highland and lowland economies and cultures. It was a contested area long before the medieval period, as the Iron Age hill-forts that dominate this area of outstanding natural beauty attest.

After the Norman Conquest, William divided the borderlands between his most-trusted men, making them the Earls of Chester, Shrewsbury and Hereford, and tasking them with containing and subduing the Welsh. They put into action a huge building programme to proclaim their mastery of the territory in a way that would also withstand fierce Welsh raids. As a result the Welsh March has the densest concentration of motte and bailey castles in all of Britain.

The March of Wales, was, to a large degree, independent of both the English Monarchy and the Principality of Wales, reflecting the need for chiefs and inhabitants who could live self-sufficiently in a place where violence was commonplace, and each church had a tower that also acted as a keep. It was a frontier land in every sense, run by ruthless, ambitious Barons beholden to no one, who fought amongst themselves as well as with the English and Welsh, and competed, sometimes fatally, for business, trade, wealth, land and status.

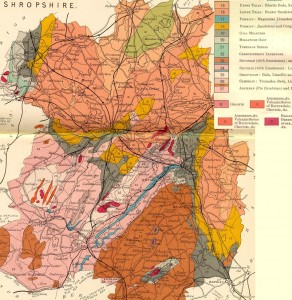

It begins to become obvious that the green and leafy peacefulness we experience today covers a bloody and fascinating history. We can go down a layer or two, under the castles of the Marcher Lords, into the substrate, and find the stone that makes this landscape so unique. An area of extraordinary geological variation, with stones from almost every period in the earth’s history and every compass point on the planet, that through its chemical content makes micro-habitats, rich soils, harsh hills, great varieties of flora, that provided resources for tools and medicine, dye and cloth.

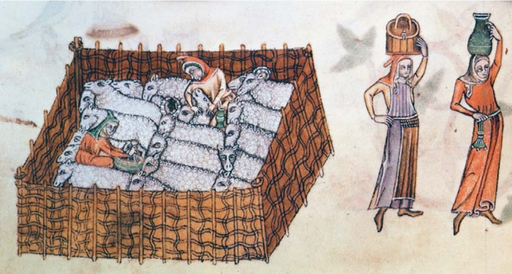

It was an area of danger and riches, but riches we may not recognise as such today. If we examine the economy of the Marches, we find that the wealth of the merchants and magnates came from the biggest export of the time, the one product that made England powerful – wool. And not just any old wool. The wool from Shropshire and Herefordshire sheep was deemed to be of the very highest quality and commanded a premium price.

Why was it so good? The sedimentary rock laid down in the Ordovician, Silurian and Devonian periods over 400 million years ago, made up of trillions of sea creatures inhabiting that temperate sea, contributed important nutrients to the soil that resulted in the ‘smooth green miles of turf’ remarked on by AE Housman (Last Poems1922), leading to the wealth of wool. And if we were to dig down into the graveyard of Saint Laurence’s Church in Ludlow, we would find the ashes of that same AE Housman, buried by a cherry tree.

Dig down deeper in that churchyard and we could find a man who had reason to thank that turf. Laurence of Ludlow (de Lodelow) was one of the greatest merchants of the medieval age, son of Nicholas, brother of John, brother-in-law of Isabel – a family who had the equivalent of a multi-million business based on the trade in wool. Like all good millionaires, they were not shy of splashing their money around. Undoubtedly they would have richly endowed St Laurence’s church in Ludlow for the good of their wealth-encumbered souls.

But their main acquisition we can see today is the manor of Stokesay (then ‘Stoke de Say’), which Laurence bought in cash from the Verdun family in 1281 and expanded considerably. It is one of the best-preserved fortified manor houses in the country, retaining both its integrity and its atmosphere. No, it is not a true castle, despite being called such. That was an important distinction. Stokesay had little military or defensive purpose. Laurence and his family had to show that they posed no threat to the power of the Marcher Lords, although the manor clearly shows their ambition to live the life of a landed lord.

But Laurence was more than an upstart merchant of the Marches, he was highly influential at court, advising the King about the wool trade with the continent. Laurence and his brother John were lynchpins in the export trade to Flanders, by turns both an ally and an enemy of England. In the year 1294, in which my latest novel begins, Laurence and John of Ludlow were at the height of their wealth and influence. Across the channel, King Edward’s Duchy of Gascony (southwest France) had been seized by the French King Philip IV, known as ‘The Fair’ (fair in appearance, not in behavior).

Edward needed to fund and raise an army to cross the sea and defeat the French. But this was harder than it used to be. Many of the Marcher Lords and Earls, as well as the knights who owed him service, refused to fight overseas. In a tight fix, he sent two brutal officers into Wales and the Marches to conscript men to serve in Gascony. The Welsh had been rebelling against the overbearing rule by the Anglo-Norman aristocracy intermittently for many years. This conscription was the final straw. When the Welsh men were mustered at Shrewsbury Castle to be sent to France, they rose up and killed the man who had conscripted them. Then, in a coordinated action, they attacked and burnt Castles across a huge area including Caernarfon, Denbigh, Ruthin, and Castell y Bere.

King Edward was now fighting wars on two fronts. And he had less money than ever.

The Ludlows advised King Edward to raise cash by tripling the customs rate on wool exports. The wool producers were outraged, as they were now going to bear the burden of financing the military operations in France and Wales. John and Laurence were sent by the King to accompany a fleet of ships loaded with wool and £25,000 worth of silver, a bribe for Edward’s continental allies in and around Flanders. He desperately needed their help to defeat the French. But a storm hit the fleet on the 26th November 1294, and several of the ships were wrecked, including the one bearing Laurence and John. Laurence’s body was found, washed up on the Suffolk coast. It was transported back to Ludlow for burial in St Laurence’s Church.

The Chronicles of the time were usually written by monks. Monks were big wool producers and, therefore, not fans of the Ludlow family. They wrote with smug satisfaction about the fate of these enormously wealthy and unscrupulous men, reporting of Laurence that ‘Because he sinned against the wool-growers, he was swallowed by the waves in a ship full of wool.’

Of John’s body we hear nothing, but his widow, Isobel, does not stay silent. She appears frequently in the medieval archive of Shrewsbury, where she kept a large townhouse backing onto the river.

Dig down into the records of this strategic town and we discover that after she was widowed so suddenly, Isobel took on the name of her first husband, Borrey, and began trading independently. This was highly unusual. It would have been normal for her to be known as ‘Isobel, once wife of John of Lodelowe’. Isobel Borrey is also recorded as a burgess of the town (the only woman in Shrewsbury to be so named). She was obviously a seasoned businesswoman and took advantage of one of the laws created by Chancellor Robert Burnell that was passed at the Acton Burnell Parliament in 1283, the Statute Merchant. This law was supposed to facilitate the administration and collection of loans by making it possible to record loans only in certain towns. Shrewsbury was one, Hereford another.

Isabel Borrey made more than thirty large loans in her own name after John’s death. She also financed a rebellion against the rightful bailiffs of Shrewsbury in 1303, and installed her own chosen men. She then sued the burgesses for the damages that occurred during the reprisals against her during the rebellion. A woman of guts, energy, ambition and determination, and for a writer, a wonderful character to bring back to life again.

The Ludlows weren’t the only high profile casualties of the unrest in the late 13th century.

If we travel down from Ludlow, at the mid point of the 257 km Welsh English border, to Gloucester at its most southern point – we are in the place where a knight of King Edward’s household was arrested in September 1295, and taken to London to be tried for treason. Sir Thomas Turberville was the first man to be executed for spying in England. And what an execution it was. There was pageantry and there was cruelty in equal measure, as this was a nobleman who had been a trusted servant of the King. But in the chaotic war for Gascony, Turberville’s loyalty was sorely tested. He was taken hostage and, for his freedom and that of his sons, he made a deal with King Philip (the not so fair) of France to pass on information about the English defences.

Sir Thomas de Turberville was part of a Norman family given land in Glamorgan and Dorset. His treachery and death became the subject of a popular anti-French ballad at the time. Much later, the de Turberville family in Dorset became notorious for another reason, when Thomas Hardy immortalized one of their louche sons in his novel, Tess of the d’Urbervilles.

Enough of the famous and infamous. The millions of ordinary people, ignored by history, are just as important, although one must delve differently to find them. Their traces remain in the shadows of ridge and furrow ploughed across the fields, the remains of pottery thrown out of badger setts. They may have been tied to the land in small villages, but they were also connected to towns, markets, and the great centres of pilgrimage by the well-trodden roads that still exist today. It was the labour of the ordinary people that built the churches, it was their feet that wore down the threshold stones, their sharpened arrows that left grooves in the doorways, their candles, lit in chantry chapels, that willed the souls of this volatile region through Purgatory to Heaven.

On the surface, this land certainly pleases the eye. It has hills and valleys of extraordinary beauty, views of distant mountains, sunken tracks roofed by trees, forested banks covered in bluebells and orchids, the colours of heather, of autumn trees and spring flowers. Church towers rise benevolently through the landscape. The ruins of castles welcome and also repel with their harsh promise of romance.

But go down a layer, or two, and there are stones and iron, bones and blood. There is ambition and feuding, love and greed, treason and artistry. It is these things that excite the imagination of a writer, that keep my heart racing to finish a story about a little known time in this very particular place. A place of many parts: ambiguity, contradiction, paradox, and paradise. It is no accident that so many artists and entrepreneurs have chosen to live here, and never to leave.

Our ambitions are alive and well in the Marches.

Kate’s second medieval novel set in the Marches, All the Winding World, (sequel to The Errant Hours) was published in June 2018.

www.kateinneswriter.com / @kateinnes2

A Tempest for our times

I do hope that all my readers are staying well. I imagine that, like me, many of you are feeling hemmed in by the worries and restrictions of this time. Hopefully this post will provide a bit of distraction – and some brain fodder.

Good Reads for Strange Times number four:

‘Hag-seed’ by Margaret Atwood

Published in 2016 by Hogarth Shakespeare and in paperback by Vintage

301 pages

This is a retelling of ‘The Tempest’ by Shakespeare.

I hope that doesn't put you off. All my teenage children now hate Shakespeare due to a combination of school exams and a well-meaning mum, convinced that they would love the plays in the end, who took them to one too many. If Shakespeare has not been to your taste up till now, I’d urge you to try this version. It’s definitely different!

In 2016, to mark the 400th anniversary of the death of the Bard, several wonderful writers were commissioned to select one of his plays and reimagine it for our time. Margaret Atwood's version of ‘The Tempest’ is the only one I've read, so far. I’ll pop the list at the end (sourced from Wikipedia) - in case you'd like to try another one of them. I quite fancy the retelling of ‘The Taming of the Shrew’ - after whose main character I was named in 1968.

Back to Hag-seed. You may know that the title is one of the insulting names given to Caliban - the monster-like servant of Prospero - the magician at the heart of the story of The Tempest. Caliban is treated badly by everyone, and blamed when this treatment leads to his offending behaviour. It is mainly but not exclusively with Caliban that Margaret Atwood's sympathies lie. And that is why in this version, her version of the play, ‘The Tempest’ is being produced by a usurped artistic director who has ended up working in a Canadian prison on an Education through Theatre project.

Rereading it, I found that by page two I'd already come across the word 'lock-down'. The inmates of the Burgess Correctional Institution are, like us, temporarily restricted in their movements, but not in their minds. They have already done MacBeth and Julius Caesar. They’ve explored the dramatic possibilities of murder and ambition. But this year, their director insists on the play of 'The Tempest' – the tale of the usurped ruler of Milan who is left for dead on an island, but whose enemies are brought within his grasp. And so it is within the play that is performed within the story of the play. Margaret Atwood enjoys messing about with these feedback loops with her incisive, driven, witty prose.

It's an addictive, sly interweaving of a character-driven modern novel with the legendary, supernatural, revenge drama, peppered with the convincing and bizarre details that Atwood creates to spark her inventions into life. It’s got her trademark nose for corruption and the worst parts of human nature, with the eventual, almost inevitable, practical acceptance of love and forgiveness. It’s got her surgical gaze at political power play - told from a victim’s point of view who is allowed to reverse his role.

I found that one of the most enjoyable aspects of the book was the rapping versions of Shakespearean verse. She pulls off these leaps from what we might think of as high to low culture with such a light, adept touch that we realise there is actually no yawning chasm between them. Here’s a little example from the prisoner ‘SnakeEye’ who is playing Antonio (the usurping brother of Prospero):

. . .

“He was stuck in his book, doin’ his magic,

Wavin’ his wand around and all that shit,

I took what I like, and that was fine,

Whatever I wanted, it was mine,

I got so used to it.

But he didn’t look, he was slack, didn’t watch his back,

What a fool, not cool, laid out the temptation,

I was bossin’ around the whole Milan nation,

He didn’t see what I took, it turned me into a crook,

Turned me into his evil twin, I went the way of sin,

Only way I could win.

So I went to the King, the Naples King,

He wanted control of that Milan thing,

So we made a deal,

He’d help me steal it, I’d pay him back,

And we grabbed my Bro, that Pros-per-o,

In the dead of night,

We paid off his guards so they didn’t put up a fight . . . “

Atwood’s humour and humanity shine from the story like a lighthouse on a rocky island. Hag-seed is a quick and engrossing read - that equally rewards rereading. I hope you enjoy it.

Other Hogarth Press Shakespeare reinterpretations:

The Gap of Time by Jeanette Winterson – a retelling of The Winter's Tale

Shylock is My Name by Howard Jacobson – an interpretation of The Merchant of Venice

Vinegar Girl by Anne Tyler – a retelling of The Taming of the Shrew

Hag-Seed by Margaret Atwood – a re-imagining of The Tempest

Macbeth by Jo Nesbø – a retelling of Shakespeare's Macbeth

Dunbar by Edward St Aubyn – which re-tells the story of King Lear

New Boy by Tracy Chevalier – a re-imagining of Othello

Additionally, Gillian Flynn is working on a re-telling of Hamlet, due for release in 2021

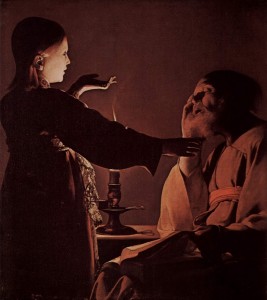

A light in the darkness

A week of isolation (in the broadest sense, as I am sharing the property with 3 teenagers, a dog, 4 chickens - and even, occasionally, my doctor husband) is already done and gone, and I wonder how you are finding it? I've been surprised at how quickly this new way of living has started to feel normal. I look at films and ads on tv of people milling about in groups, hugging and kissing, and wonder why they are taking so few precautions. Shouldn’t they be more wary? Where on earth are their masks and gloves?!

I think about going out to get provisions and a great weariness overwhelms me. It's so demanding and stressful negotiating public spaces. Better to stay at home and, hopefully, harm no one.

I suppose it is one of the great abilities of our species that we so quickly adapt to new circumstances and environments. And that is a good way into thinking about my next book recommendation to you - 'Bearmouth' by Liz Hyder. Published in 2019 by Pushkin Press.

In the spirit of full disclosure, Liz is a writer friend of mine. I remember the moment, sitting in her front room, when she told me about her nearly finished YA book set in a fictionalised Victorian mine. At the time I thought "what a fabulous title!"

Now, six months after its publication, I can tell you that the content more than matches the cover.

The main character is one of the young mine workers, Newt, and the story is told in Newt's unique voice and language, (which takes only two or three pages to get used to - especially if you have a phonetic speller in your household, as I do). The men, boys and (secret) girls in the mine are all subject to the most rigid form of isolation. Newt hasn't seen daylight since the age of four. The workers are exploited, and kept ignorant of their rights. The masters exert their authority ruthlessly, with tiny rewards and a twisted form of religion.

Sounds dark - and it is, literally and figuratively. But there is so much humanity in Bearmouth - as we also see at this dark time in our own society. People help each other, even at risk of their own death. People give hope to each other, and like the rare candles in the dark of the mine, strength, compassion and love shine out in the darkness. The mine is a microcosm of society, and the plot shows how courage and vision can change even the most entrenched evil.

I read Bearmouth in one sitting, on a plane on my way to see my dad in the US (and doesn't that feel like another era already?) I was utterly immersed in a story that flows like water through an underground cave system, carrying you on to the inevitable waterfall of freedom. Forgive me the poetic licence, please. What I am trying to say is that 'Bearmouth' will grab you and not let you go - taking you through the darkest places and then, so satisfyingly, into starlight.

Although marketed as a Young Adult novel, and shortlisted for the Waterstones Children's Books of the Year 2020, 'Bearmouth' is a great adult read too.

I hope you enjoy it as much as I did.

Hopefully not a thousand and one nights in lockdown

Distraction. It can be good, it can be bad.

We probably all know a bit about distraction on social media. When I've spent too long scrolling through Twitter or Facebook, I often feel sheepish. A bit ashamed. 'Shouldn't you be spending ALL your time in constructive pursuits?' I demand of myself.

We can be pretty harsh on ourselves.

But it is something that eats away at concentration, and I would like to do it less and get the scales of my time better balanced.

Then there is the good kind of distraction. At the moment, I don't want to think about the possibility of members of my family who work in the NHS becoming ill. If I think about it too much, I might frighten the children with my anxiety. And to distract myself from thinking about that, I read, I write, I research, I watch films. I look out at the world. There is so much to think about.

Good distraction leads the mind away from mithering over hurts or potential disasters. A toddler who is about to lose their temper about a fallen ice cream can often be placated with a balloon, and in the same way, our monkey mind can sometimes be redirected from destructive ruminating by something new, exciting and shiny.

My third recommendation for a good read for this extraordinary time is 'One Thousand and One Arabian Nights' written by Geraldine McCaughrean (Oxford Story Collections edition). I think everyone knows a little bit about 'The Arabian Nights'. I only knew the bare bones before getting hold of this version and taking it on a holiday in a camper van through Norway (not the most appropriate context!). What I was not prepared for was the humour, the modernity, the cunning, the poetry, and the beauty of the stories, embedded in the embracing arc of revenge and love rendered so movingly by Geraldine McCaughrean.

This is often marketed as children's fiction - Sinbad the Sailor, Ali Baba, Ala al-Din and his wonderful lamp (and this version is suitable for children) - but 'The Arabian Nights' is more than just those disneyfied tales. It is a collection of stories for all ages, that have their origin in the oral tradition of Asia and the Middle East, when the long, dark nights of the desert could be made more enjoyable by sharing tales and music around a fire.

These tales were written down perhaps as early as the 8th century AD, and certainly by medieval times, but the original, oral tales are much older - stretching in time and place to the great dynasties of India and Persia - with Arabian tales added later. There are lots of adventures and burlesques, but also more subtle tales of tricks, thieves, fables, scolds - all giving an insight into the abiding human condition. (The erotica is omitted from this edition - you may be disappointed to hear - but there are many other versions to choose from.)

At the heart of the tale is the clever story teller, Shahrazad, who must distract her husband, King Shahryar, every night with a new story. He is determined to exact revenge on women in general for his first wife's betrayal and infidelity, ('Woman's love is as long as the hairs on a chicken's egg' he tells her. If any writers amongst you require simile or metaphor inspiration, it is here in abundance) by beheading a new wife every morning. Shahrazad is his thousandth bride. Scholars have explained her away as a frame for a collection of Arabian tales - a bit like The Decameron or the semi-legendary events around the creation of 'Frankenstein' by Mary Shelley.

But Shahrazad is not consigned to being merely a wooden frame for the tales in this version. She is a quick-thinking woman of foresight, bravery, resourcefulness and passion. She knows the power of story to distract and redirect. Her strength is in her ability to create new worlds for her psychopathic husband to inhabit every night, worlds in which he doesn't have to be revengeful and angry. Where he can see all sides of an event, rather than just one point of view. Where he can become someone else.

The stories she marshals to keep the King from ordering her death are very entertaining. But her management of her husband's moods and insecurities is a master class in the best kind of manipulation. I suppose her ability to fall in love with a serial killer could be a mark against Shahrazad, but as she converts him to reasonable behaviour in the end, and it is a story not real life, I think we ought to let her off.

I wonder if the creator of the story of Shahrazad was a woman. I really appreciate the way Geraldine McCaughrean, the contemporary storyteller, has explored her inner thoughts and her relationship with her younger sister. But whoever it was, they have brought Shahrazad and her rich store of tales to life for countless listeners and readers from all genders, ages and nationalities, for thousands of years.

So I hope you enjoy her tales and embrace the distraction, at least for a while.

Reading through Lockdown

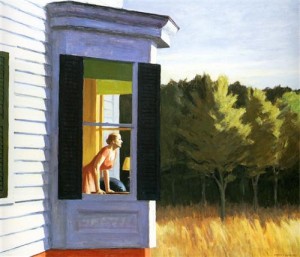

Who knows when our lives will feel 'normal' again? I suspect that there are certain things we will never, ever take for granted in the future. A drink with friends - a hug with an older relative - a trip to a beautiful art gallery or museum - travelling to visit family. It's good to be reminded that these things are wonderful, important, nurturing - and fragile.

I believe that all the writing courses I was due to run early this year will have to be cancelled. The talks and presentations to various groups as well. I hope to keep writing, but the opportunity to concentrate is elusive. However, there is something I can do (besides write books and keep my three teenagers from consuming all the food in the house in one day). I'm going to try to suggest a good book every week for the next little while, hoping that reading them provides consolation and distraction.

Books give you a place to go when you have to stay put. They are escape hatches into another reality. They are secret gardens to hide in. They are forests in which you can lose your way and your worries - at least temporarily. These will all be books I've read, and some will be particularly suitable for a time of isolation.

Book Number One: The Siege - by Helen Dunmore. Setting: Leningrad in WW2 Published: 2001 This book blew me away when I first read it. The quality of the writing, the intensity of the situation and the believable characters made it one of my all time favourite books.

The subject matter is grim. Leningrad was starved. The people lived through bitter cold, famine and brutality. But the outcome is an uplifting, unforgettable narrative about family, love, commitment and true grit. The tenderness with which each relationship is detailed, and the way Helen Dunmore expresses the appreciation of small objects of comfort make this a very memorable and important read for these times.

I highly recommend this book, and I also recommend you order it from your local independent book shop - which will be able, most likely, to send it to you. There are always audio book options and ebooks too.

This book may help us to see that our lock down is quite luxurious by comparison. Perspective and context is everything! I hope you enjoy it. I hope you stay well in the midst of this frightening pandemic. I wish you strength.

Bad Guys Make Good Plots

Recently I was asked to contribute a guest post to the fabulous 'History Girls' Blog. This is a group of best-selling writers of historical content, fiction, non-fiction, for children and adults. Needless to say, I was delighted to be part of it, and here is the blog I wrote - about the necessity of a good villain.

A story needs a villain – someone to get the action going and make the protagonist look heroic. This is as true for historical fiction as it is for any other kind. We love to shiver at their evilness and then gloat as they get their comeuppance. And history certainly has plenty of real villains to choose from for the historical novelist. It is jam-packed with good material for bad guys.

In All the Winding World, my latest medieval novel set in the late 13th century during the Anglo-French War, one particular historical character galloped into the plot displaying all the necessary qualifications. Rich, cruel, self-centred, eccentric, creepy, sadistic – Robert II Count of Artois had it all. Including a gory and well-deserved demise.

You’ve probably never heard of him. Neither had I. Born in 1250 AD, he was the son of Count Robert I and Matilda of Brabant – and nephew of the sainted King Louis IX of France. However, the piety of his uncle had not rubbed off. Count Robert II was a hedonist with the means to satisfy all his many and varied desires. At birth he had inherited the wealthy territory of Artois on the border between France and Flanders, as his father was already dead when he was born.

Over the course of his early life, he became a ruthless and talented military leader, taking part in many of the wars that were prevalent in the 13th century. He married three times and had several mistresses. This was not unusual, as women were highly likely to die in childbirth. So, based on this brief biography, perhaps you could say that he was a typical aristocrat of the time.

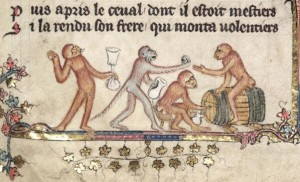

But his choice of pets was a real giveaway that he was villain material. The Count of Artois was known to keep a pet wolf, which he allowed to hunt across his lands, eating the herds of the local peasants (hopefully not the peasants themselves). He had a large castle and walled park at Hesdin (now Vieil Hesdin) in Boulogne North East France stretching over eight hundred hectares, which he filled with the most extraordinary attractions. The Count was said to enjoy practical jokes, and his park was designed to freak people out in many imaginative ways. If you’d like to know what it might have looked like, a detail of a painting can be viewed on this website: http://www.medievalcodes.ca/2015/04/the-marvels-of-hesdin.html

We often think that medieval people had little in the way of what we would call ‘technology’. But this was not so. As well as real exotic animals, Hesdin housed automata – skillfully constructed mechanical beings that moved, ‘spoke’ and frightened the guests. In a later set of accounts, these were described as including a talking mechanical owl, caged birds that spat water, and waving monkeys covered in badger fur. I can think of several horror films featuring this kind of thing.

The park also provided numerous ways of being dunked in water and covered in soot or flour. All designed apparently to amuse, if not the victim, then certainly the Count. The engineers who made these marvels would have employed devices used in both agriculture and the military, and their inventions were to have a profound impact on William Caxton, the first man to run a printing press in England when he visited it in the 15th century.

But I digress. If a story has a villain, it follows that he must get his just deserts. It happened to the Count a few years after the action of my novel, but it was worth waiting for.

Robert, along with the cream of the French aristocracy, rode into Flanders in July 1302, to teach the region a lesson. After two years of brutal occupation and unrest, the people of Flanders had revolted against the French rule in May 1302 and killed many Frenchmen in Bruges. King Philip IV sent in 8,000 men to quell the uprising and put Count Robert II of Artois in charge. But when the two armies met outside the town of Kortrijk (Courtrai) on the 11th July in what came to be know as the ‘Battle of the Golden Spurs’, all did not go as the French had planned.

The French cavalry proved to be no match for the Flemish infantry and their pike formation. In the end, three hundred noblemen of France were slaughtered by the yeomanry of Flanders. In revenge for French cruelty, they took few if any knights prisoner, counter to the usual practice of holding nobles for ransom. Count Robert was one of those to be killed, in a most satisfying and humiliating way.

Robert of Artois was surrounded and struck down from his horse by an extraordinarily big and strong Cistercian lay brother, Willem van Saeftinghe. According to some tales, bleeding from many wounds, Robert begged for his life, but the Flemish refused to spare him, claiming that ‘they did not understand French.’

This is what the Annals of Ghent had to say about the matter:

“. . . the art of war, the flower of knighthood, with horses and chargers of the finest, fell before the weavers, fullers and the common folk and foot soldiers of Flanders . . . the beauty and strength of that great French army was turned into a dung-pit, and the glory of the French made dung and worms.”

‘Good riddance!’ one can almost hear the fed-up peasants of Artois cry.

(All images Public Domain)

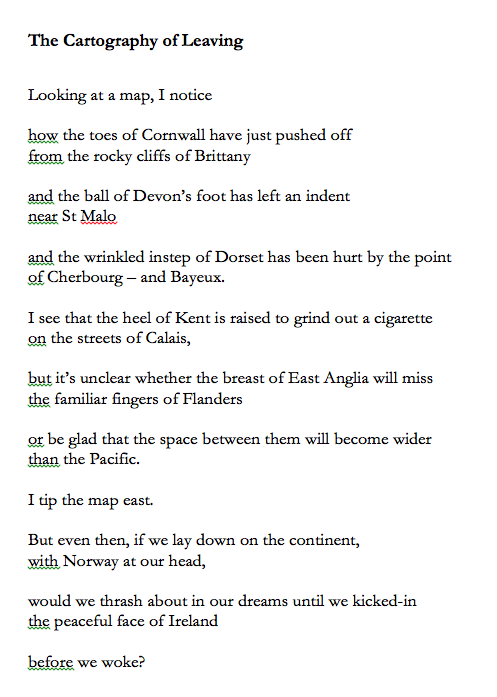

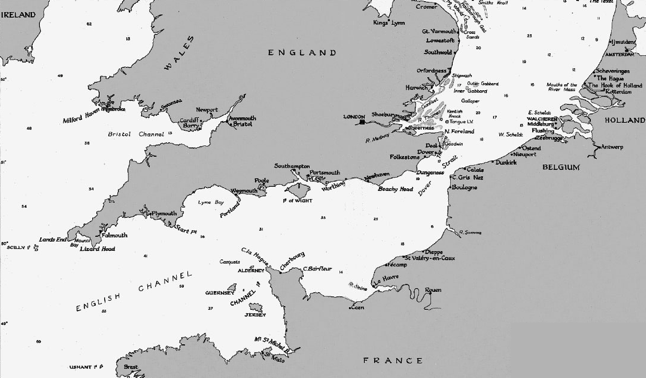

The Cartography of Leaving

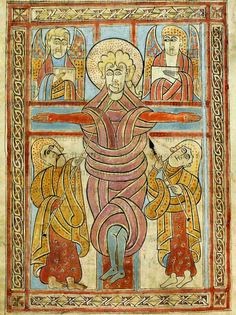

It was early December 2018, and I was in Shrewsbury Library filling a rare empty half-hour between appointments. I often gravitate to a particular reading room in that library - covered in graffitied wood from its days as a boys school. Giving in to my fondness for ancient cultures, I chose a book of medieval art and sat down to browse through its pages.

Close to the beginning of the book I found a map of Europe. I looked at it carefully, and the longer I looked at it the more I saw the print of the UK on the coast of France and the other countries along the Channel - and their imprint on us. Geologists have long known that the two land masses were very recently (at least in geological time) connected.