|

| Elephant drinking from the Zambezi River |

I have recently returned from a return visit to Zimbabwe and Southern Africa. It was a journey that will provide grist for my mind’s mill for years to come. But, at this very early stage of processing, I find it is the elephant and its behaviour which must be explored first.

It is interesting that, until the medieval period, elephant were endemic to the whole of the African continent. The extinction in Northern Africa (around a thousand years ago) occurred as a direct result of the ivory trade, to provide ecclesiastics and aristocrats with beautiful, prestigious artworks. Ivory has been sought after and worked for millennia. It is very hard, lasts indefinitely, doesn’t splinter and can be carved into the most intricate of forms. Medieval craftsmen felt its pale purity was particularly suited to representing the Virgin Mary.

|

Virgin and Child, carved in elephant ivory

1320-30 in Paris, Victoria and Albert Museum

(note the contrapposto of the virgin, which is demanded by the curve of the elephant tusk) |

In medieval symbolism, elephants were almost as common as dragons, and similarly credible. They belonged to the semi-mythic world of the Bestiaries; books of quasi-religious natural history. The Bestiaries were didactic and precise about both the elephant’s habits and their meaning for the enquiring Christian mind. Even then the elephant’s concern for its family, the younger members in particular, was noted, as well as their prodigious intellect and memory. They were said to be symbolic of Christ himself. Their main enemy was the dragon, which, when they were in water to give birth, would bite them and attempt to drag them down to the depths. The dragon is always symbolic of the devil, and the elephant fought with it as Christ did with Satan.

|

|

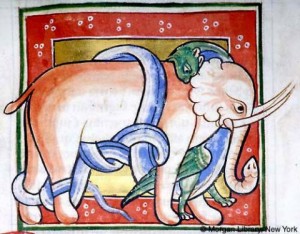

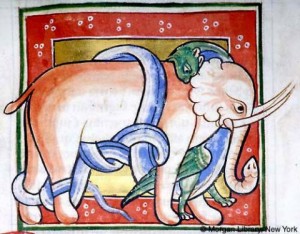

The eternal battle between the Dragon and the Elephant

from the Worksop Bestiary, MS M. 81

12th century, Pierpont Morgan Library

|

Although it is a digression, I cannot help but draw a parallel with the story of The Elephant’s Child by Rudyard Kipling. In this cautionary myth, the usual outcomes are turned on their head as, instead of being killed by his ‘insatiable curtiosity’, the hero of the tale actually gains the elephant’s most useful and distinctive feature: his trunk. The crocodile (a dragon by any standard), pulled his little nose into ‘a really truly trunk, such as all elephant’s have today’ during its attempt to drag the young elephant into ‘the great grey-green greasy Limpopo river’, to eat him. With his advantageous trunk, the Elephant’s child was then able to mete out revenge on his ‘dear family’ who had subjected him to repressive spanking all his life for being too curious. A story to gladden the hearts of liberal educators everywhere.

|

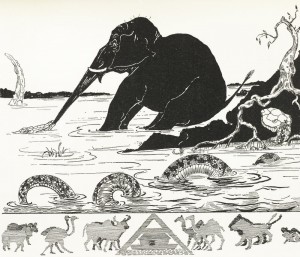

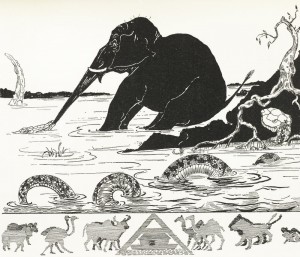

An illustration from The Elephant’s Child, Rudyard Kipling

(note also the bi-coloured python rock snake which we had the privilege to hold during our trip) |

We saw many elephants during our five week trip. In one day in Hwange National Park, we saw over two hundred. It was awe inspiring, it was mesmerising. We were able to see for ourselves the way family groups protect their young, the exuberance of the young bulls, the clumsy drinking and bathing of the elephant children, the command of the matriarchs.

But, from the comfort of my desk in Britain, I am now trying to make sense of what is happening to the elephant in Southern Africa, and what this means for its future. We saw far more elephant on this trip than we did in the two years we worked in Zimbabwe between 1992-94. The concentration of the herds in the National Parks has surged dramatically. We also saw elephant on the road side in Victoria Falls and on the shore of Lake Kariba. Elephants are increasingly able to live only in tourist areas, as the African population relying on subsistence agriculture can ill afford to have their crops flattened. And the threat of poachers is ever present. The demand for ivory from the far east, Singapore, Japan and China in particular, is stronger than ever, and the potential gain in hard currency as well as bush meat, is difficult to resist.

At Chitsungo Mission in the Zambezi Valley, we met Colin, a friendly and focussed young man, who was very open about his past. He spent four years in prison for killing seven elephants and trading the ivory. In prison he was taught how to crochet and converted to Christianity. Now he is trying to make a living from his craft, and is desperate for help to fund his production and market his goods. He wants nothing more to do with poachers, or prisons.

|

| Colin and models with his crochet goods: caps, rucksack, and tablet case |

Meanwhile the rising middle class in China can now afford high-status ivory products, and the demand is growing. The curbs on the ivory trade, negotiated through CITES, (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna) have largely been ignored. Robert Mugabe, Zimbabwe’s ever-present President, has even been accused of bartering tonnes of ivory for weapons with China, breaking his country’s commitment to CITES.

The issues around elephant conservation and the ivory trade are very complex, and I cannot pretend to understand them all. Nor do I feel able to lecture those in Africa who kill elephants in order to protect their livelihood, or to make a living. What would I be willing to do if my children were desperately hungry? As one of my former pupils explained when I met him in Harare: “For us elephants are normal, and more of a pest than an attraction.”

But I find it horrifying to contemplate their slaughter.

Because they are killed so brutally. No quick well-managed death for them, as we want for our sheep and cattle here in the west.

Because there are such strong bonds between them. From all behavioural evidence, they love and they grieve.

Because they are extraordinary, perfectly adapted animals, who despite their size can be remarkably gentle, and who can walk with deliberation through the narrow paths of the bush and disappear like smoke.

“It is a fact that Elephants smash whatever they wind their noses round,

like the fall of some prodigious ruin, and whatever they squash with their feet they blot out.

They never quarrel about their wives, for adultery is unknown to them.

There is a mild gentleness about them, for if they happen to come across a forwandered man in the deserts, they offer to lead him back into familiar paths. If they are gathered together into crowded herds, they make way for themselves with tender and placid trunks, lest any of their tusks should happen to kill some animal on the road.

If by chance they do become involved in battles, they take no little care of the casualties, for they collect the wounded and exhausted into the middle of the herd.”

(From The Book of Beasts, a translation of a 12th century Latin Bestiary, Cambridge University Library 11.4.26 by T.H. White, 1954)

It seems that elephants could teach us much about ‘humanity’.

|

| An elephant family in Hwange National Park, 2015 |