I am very grateful to my friend, Vuyelwa Carlin, for reading and reviewing ‘Wild Labyrinth’ with such insight and commitment. Vu and I have been members of the Borders Poetry Writing Group for several years, and I admire her skill as a poet and value her opinion very much.

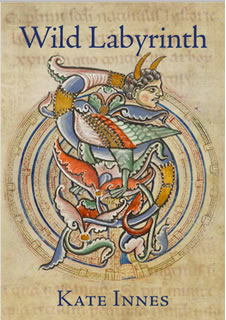

‘Wild Labyrinth’ by Kate Innes

This is the third in Kate Innes’ Arrowsmith historical novel trilogy, set in the late 13th / early 14th century. As always, the historical background is very impressive; and as should be with a trilogy, this last book is the best. All three are very good; but Wild Labyrinth is riveting from page one. Time has passed between the second book, All the Winding World, and this one: Illesa has suffered a miscarriage, losing a daughter; also, the reader gradually realises, she and her husband Richard are at odds. Chapter one opens (after an intriguing and atmospheric Prologue) with their son Christopher being sworn in as a knight for an unpopular war (it is 1306, near the end of Edward the First’s reign) in a packed, noisy Westminster Abbey; the atmosphere is anxious, sorrowful and unnerving, setting the scene for much of the book. This disquiet is unsettling, but not off-putting – on the contrary, it enriches the book. The book’s characters – not least Illesa and her family – are complex, faulty people; very realistic. They are mostly sympathetic and attractive, with all their imperfections; but there are two at least who are highly ambiguous – full of wit, a charm which may or may not be manipulative, and an uneasy oddness; part of the writer’s skill is that the reader is kept guessing for some time as to their real natures: are they to be trusted?

The narrative, very adventurous, often tense, sometimes horrifying, goes along at a good pace right from the start; as I said, the book is a page-turner. The story is of journeys made – in more senses than one: by Illesa, her family and their manservant William, and by the maker of the long-famous and treasured Mappa Mundi, who joins them as an eager but highly temperamental guide. This last is a beautifully realised character; the few facts known about him have been combined with a very creative imagination to build up a moving portrait. Richard Oriosus, a scholar and artist of genius, is difficult, obsessive, puzzling and contentious, a man of suffering and regrets; in the end, he is deeply sympathetic. It is he who speaks the highly evocative Prologue, describing the making of the map, the first of several fascinating accounts, encompassing as they do his brilliance, his almost fixated dedication to his work, and of course the state of knowledge of the world: “… I drew the centre of the world – Jerusalem’s wall encompassing the dome of the Holy Sepulchre…” To him, the map is an artistic endeavour to the glory of God – bound up too with his own past; a profound sorrow is hinted at. To others, such as his Bishop, it is mainly a means of attracting pilgrims hoping for miracles, and their donations. Here, as we realise – he doesn’t mention her name – he first meets, and remembers, Illesa.

The book immerses the reader in the past of over seven hundred years ago: its strangeness and also its familiarities. Kate Innes knows her subject extremely well; she has imagined herself, with vivid accuracy, into ways of thinking and beliefs that in some ways are alien to us. But the characters are completely believable. We human beings have changed so completely in some ways; and so little in others. This is part of the fascination of history. What strikes me particularly (as with the other two books) is the way in which people’s lives are soaked through with religious belief. Everything that happens is explained, one way or another, in accordance with a faith that is taken as read; an engagement with a God of sometimes disturbing and incomprehensible ways, and complex angers. What strikes me is that this is not described from above, as it were – that is, from a position of implied superiority; the writer understands and respects – implicitly sifting obvious superstitions from possible truths – the absolute conviction of those days that God was intimately involved with human affairs. This encouragement to think ourselves into a different time does not always preclude dramatic irony: for example, there is a painfully moving account of what is clearly bipolar disorder: the reader knows this at once, but for the sufferer it is an affliction imposed upon him by God, which (however imperfectly he understands the reason) he must endure.

It is also brought home to us how shockingly dangerous, especially for women – and how long, cumbersome and uncomfortable – travel was in those days.

This is a many-layered book; the story is a dense mesh, wide-ranging and excellently plotted, full of real people about whom one is curious, and detailed information about their everyday lives, assumptions and knowledge: we inhabit the peculiar atmosphere of a distant past. The author’s wide knowledge does not intrude, however (I have read novels where the research gets in the way) but is bound in as a whole with the story. No spoilers, but I very much liked the endings: there are two of these, as characters part ways.

Vuyelwa Carlin