A tabby cat enjoys watching a patch of sunlight in the peaceful, cordoned-off area in front of the main altar of Wells Cathedral

During a fascinating research trip to Hailes Abbey and Wells Cathedral, I was struck by the number and variety of animals I found in these well-preserved sacred contexts. Our age, on the whole, seems to disapprove of animals in church, as if somehow their animal nature made them inappropriate in the humanly constructed holy space.

This was not the case in Medieval art. Animals appear in abundance, taking on roles as faithful companion, indicator of nobility and symbol of just about every virtue and sin. They are painted on the walls, sculpted in the ceiling bosses and climb around the column capitals. They wind around the font and patter along the floor tiles. They look down from the highest heights, and mischievously up from below as part of misericords, little seats which supported the bottoms of monks and priests in church.

A boss from the ceiling of Hailes Abbey Chapter House, showing either Jesus fighting the Devil in the form of a lion, or Samson and the Lion

In this way, the churches constructed and decorated by medieval people mirrored the natural world outside, rather than making a ‘better’ separate space for worship. The church was a place for people to learn what the natural world meant in the heavenly plan, and every last animal had its role to play and its lessons to teach.

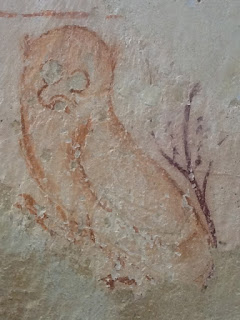

A short-eared owl from Hailes Parish Church (13th century), an adorable animal supposed to represent sin and darkness

The Medieval Bestiaries (about which I have written more here: robin redbreast post) were very eager to tie up the behaviour of animals, whether real or imaginary, with their spiritual significance. This is not an area of theology pursued in modern times, but perhaps the celebration of and identification with the natural world should be more encouraged. The many animals in danger of extinction could certainly stand as symbols of human indifference and greed in a modern iconography.

A hybrid elephant from Hailes Church

During the Reformation a rift occurred between image and word, between the natural world with all its instructive behaviour and the spirituality of the intellect. Natural representations were covered or destroyed by those who wished to emphasise the primacy of the revelation of God through the word, the Bible, rather than through creation. This is obviously a vast oversimplification of the profound and violent change that the western church underwent at that time, but it is one of the obvious effects for people exploring the development of sacred buildings.

In my opinion, it is only when nature and humankind, image and word, intellectual and physical are joined together that we come anywhere near being able to express the Divine.

The tabby settles down for a nap in front of the altar of Wells Cathedral

A fragment from Jubilate Agno by Christopher Smart (1722-1771)

For I will consider my Cat Jeoffry.

For he is the servant of the Living God, duly and daily serving him.

For at the first glance of the glory of God in the East he worships in his way.

For is this done by wreathing his body seven times round with elegant quickness.

For then he leaps up to catch the musk, which is the blessing of God upon his prayer.

For he rolls upon prank to work it in.

For having done duty and received blessing he begins to consider himself.

For this he performs in ten degrees.

For first he looks upon his forepaws to see if they are clean.

For secondly he kicks up behind to clear away there.

For thirdly he works it upon stretch with the forepaws extended.

For fourthly he sharpens his paws by wood.

For fifthly he washes himself.

For sixthly he rolls upon wash.

For seventhly he fleas himself, that he may not be interrupted upon the beat.

For eighthly he rubs himself against a post.

For ninthly he looks up for his instructions.

For tenthly he goes in quest of food.

For having considered God and himself he will consider his neighbour.