“Once people come here, they never leave. It is the graveyard of ambition.”

When I first came to live in Shropshire, I heard this quite a lot. Now that I’ve been here nearly a quarter of a century, I see that at least some of this statement is true. Certainly I never want to leave this area and hope to live a long life amongst its hills and woods. But there is so much more to this saying than first meets the eye, or the ear. Perhaps your ambition is simply to live connected with nature amongst friendly people with relatively uncluttered roads. Or perhaps it is to live in a landscape that inspires and informs – that oozes atmosphere and ancient significance. I feel I have fulfilled both these ambitions, and even more than that – I’ve turned them into a job.

As an archaeologist and museologist, I have always enjoyed living in the past. As a writer, I particularly like to live in the medieval period, and even more particularly, I like to live in the last quarter of the thirteenth century in the Welsh Marches. Perhaps you, like me, understand that there are some locations in the world where the barrier between the present and the past is thick and strong. I’ve lived in a few of those soulless places. They usually have plenty of shopping malls. But there are other places where the boundary between present and past seems as insubstantial as gauze.

In the Marches, we can easily reach back across centuries. We sense it in the shiver down the spine in a darkened church, or the overwhelming feeling of presence when we walk alone down an ancient hollow way, or stand near one of the many veteran oak or yew trees. There is the sudden and uncanny knowledge of the many footfalls that went before us, still echoing. For me this happens particularly in medieval monuments, but I know others who feel the same about prehistoric or even Victorian locations. The Marches has plenty of history thrills for all persuasions. But for now let’s look at the late thirteenth century. Let me try to explain the attraction.

It was a time when the charismatic and peripatetic King Edward the First (later to be known as the Hammer of the Scots) travelled through this landscape repeatedly in his attempt to subdue the Welsh and appease the powerful Marcher Lords.

It was a time of conflict with the tenacious Welsh Princes – Llewelyn ap Gruffydd, Dafydd ap Gruffydd, Rhys ap Maredudd, and Madog ap Llewelyn, who refused to be cowed, who kept harassing the Anglo-Normans with hit and run raids and ancient guerrilla tactics. Their bands of Welsh infantry were armed with scramasax knives and spears, weapons for close quarter fighting. They harried the English interlopers who were intent on taking their land and their stock.

It was a time when the second-most powerful man in the kingdom was a Shropshire lad, Chancellor Robert Burnell, one of the greatest legislators of all time who lovingly crenellated his natal home of Acton Burnell.

‘The Graveyard of Ambition’ seems a rather negative label. However, it is not without its useful aspects. As a former archaeologist, I tend to view graveyards in a slightly more positive light than most people. I’ve spent some time excavating them, and I understand that they hold a huge amount of information – about the economy, the environment, the social hierarchy, and religious beliefs in the past. Yes, there are plenty of dead, decaying bodies, but they are very interesting dead bodies. The older they are the more interesting, in my view. And if one must see the Welsh March as a graveyard, it is certainly one of the most intriguing graveyards in Britain. The boundary that meanders between Wales and England, in eddies and oxbows of territory disputed for thousands of years, is essentially a boundary of topography, between highland and lowland economies and cultures. It was a contested area long before the medieval period, as the Iron Age hill-forts that dominate this area of outstanding natural beauty attest.

After the Norman Conquest, William divided the borderlands between his most-trusted men, making them the Earls of Chester, Shrewsbury and Hereford, and tasking them with containing and subduing the Welsh. They put into action a huge building programme to proclaim their mastery of the territory in a way that would also withstand fierce Welsh raids. As a result the Welsh March has the densest concentration of motte and bailey castles in all of Britain.

The March of Wales, was, to a large degree, independent of both the English Monarchy and the Principality of Wales, reflecting the need for chiefs and inhabitants who could live self-sufficiently in a place where violence was commonplace, and each church had a tower that also acted as a keep. It was a frontier land in every sense, run by ruthless, ambitious Barons beholden to no one, who fought amongst themselves as well as with the English and Welsh, and competed, sometimes fatally, for business, trade, wealth, land and status.

It begins to become obvious that the green and leafy peacefulness we experience today covers a bloody and fascinating history. We can go down a layer or two, under the castles of the Marcher Lords, into the substrate, and find the stone that makes this landscape so unique. An area of extraordinary geological variation, with stones from almost every period in the earth’s history and every compass point on the planet, that through its chemical content makes micro-habitats, rich soils, harsh hills, great varieties of flora, that provided resources for tools and medicine, dye and cloth.

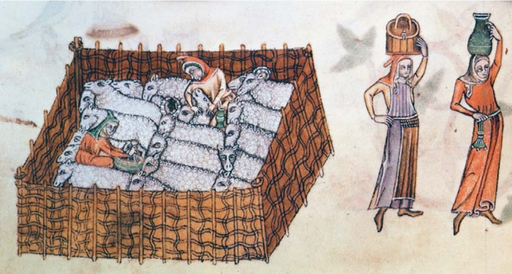

It was an area of danger and riches, but riches we may not recognise as such today. If we examine the economy of the Marches, we find that the wealth of the merchants and magnates came from the biggest export of the time, the one product that made England powerful – wool. And not just any old wool. The wool from Shropshire and Herefordshire sheep was deemed to be of the very highest quality and commanded a premium price.

Why was it so good? The sedimentary rock laid down in the Ordovician, Silurian and Devonian periods over 400 million years ago, made up of trillions of sea creatures inhabiting that temperate sea, contributed important nutrients to the soil that resulted in the ‘smooth green miles of turf’ remarked on by AE Housman (Last Poems1922), leading to the wealth of wool. And if we were to dig down into the graveyard of Saint Laurence’s Church in Ludlow, we would find the ashes of that same AE Housman, buried by a cherry tree.

Dig down deeper in that churchyard and we could find a man who had reason to thank that turf. Laurence of Ludlow (de Lodelow) was one of the greatest merchants of the medieval age, son of Nicholas, brother of John, brother-in-law of Isabel – a family who had the equivalent of a multi-million business based on the trade in wool. Like all good millionaires, they were not shy of splashing their money around. Undoubtedly they would have richly endowed St Laurence’s church in Ludlow for the good of their wealth-encumbered souls.

But their main acquisition we can see today is the manor of Stokesay (then ‘Stoke de Say’), which Laurence bought in cash from the Verdun family in 1281 and expanded considerably. It is one of the best-preserved fortified manor houses in the country, retaining both its integrity and its atmosphere. No, it is not a true castle, despite being called such. That was an important distinction. Stokesay had little military or defensive purpose. Laurence and his family had to show that they posed no threat to the power of the Marcher Lords, although the manor clearly shows their ambition to live the life of a landed lord.

But Laurence was more than an upstart merchant of the Marches, he was highly influential at court, advising the King about the wool trade with the continent. Laurence and his brother John were lynchpins in the export trade to Flanders, by turns both an ally and an enemy of England. In the year 1294, in which my latest novel begins, Laurence and John of Ludlow were at the height of their wealth and influence. Across the channel, King Edward’s Duchy of Gascony (southwest France) had been seized by the French King Philip IV, known as ‘The Fair’ (fair in appearance, not in behavior).

Edward needed to fund and raise an army to cross the sea and defeat the French. But this was harder than it used to be. Many of the Marcher Lords and Earls, as well as the knights who owed him service, refused to fight overseas. In a tight fix, he sent two brutal officers into Wales and the Marches to conscript men to serve in Gascony. The Welsh had been rebelling against the overbearing rule by the Anglo-Norman aristocracy intermittently for many years. This conscription was the final straw. When the Welsh men were mustered at Shrewsbury Castle to be sent to France, they rose up and killed the man who had conscripted them. Then, in a coordinated action, they attacked and burnt Castles across a huge area including Caernarfon, Denbigh, Ruthin, and Castell y Bere.

King Edward was now fighting wars on two fronts. And he had less money than ever.

The Ludlows advised King Edward to raise cash by tripling the customs rate on wool exports. The wool producers were outraged, as they were now going to bear the burden of financing the military operations in France and Wales. John and Laurence were sent by the King to accompany a fleet of ships loaded with wool and £25,000 worth of silver, a bribe for Edward’s continental allies in and around Flanders. He desperately needed their help to defeat the French. But a storm hit the fleet on the 26th November 1294, and several of the ships were wrecked, including the one bearing Laurence and John. Laurence’s body was found, washed up on the Suffolk coast. It was transported back to Ludlow for burial in St Laurence’s Church.

The Chronicles of the time were usually written by monks. Monks were big wool producers and, therefore, not fans of the Ludlow family. They wrote with smug satisfaction about the fate of these enormously wealthy and unscrupulous men, reporting of Laurence that ‘Because he sinned against the wool-growers, he was swallowed by the waves in a ship full of wool.’

Of John’s body we hear nothing, but his widow, Isobel, does not stay silent. She appears frequently in the medieval archive of Shrewsbury, where she kept a large townhouse backing onto the river.

Dig down into the records of this strategic town and we discover that after she was widowed so suddenly, Isobel took on the name of her first husband, Borrey, and began trading independently. This was highly unusual. It would have been normal for her to be known as ‘Isobel, once wife of John of Lodelowe’. Isobel Borrey is also recorded as a burgess of the town (the only woman in Shrewsbury to be so named). She was obviously a seasoned businesswoman and took advantage of one of the laws created by Chancellor Robert Burnell that was passed at the Acton Burnell Parliament in 1283, the Statute Merchant. This law was supposed to facilitate the administration and collection of loans by making it possible to record loans only in certain towns. Shrewsbury was one, Hereford another.

Isabel Borrey made more than thirty large loans in her own name after John’s death. She also financed a rebellion against the rightful bailiffs of Shrewsbury in 1303, and installed her own chosen men. She then sued the burgesses for the damages that occurred during the reprisals against her during the rebellion. A woman of guts, energy, ambition and determination, and for a writer, a wonderful character to bring back to life again.

The Ludlows weren’t the only high profile casualties of the unrest in the late 13th century.

If we travel down from Ludlow, at the mid point of the 257 km Welsh English border, to Gloucester at its most southern point – we are in the place where a knight of King Edward’s household was arrested in September 1295, and taken to London to be tried for treason. Sir Thomas Turberville was the first man to be executed for spying in England. And what an execution it was. There was pageantry and there was cruelty in equal measure, as this was a nobleman who had been a trusted servant of the King. But in the chaotic war for Gascony, Turberville’s loyalty was sorely tested. He was taken hostage and, for his freedom and that of his sons, he made a deal with King Philip (the not so fair) of France to pass on information about the English defences.

Sir Thomas de Turberville was part of a Norman family given land in Glamorgan and Dorset. His treachery and death became the subject of a popular anti-French ballad at the time. Much later, the de Turberville family in Dorset became notorious for another reason, when Thomas Hardy immortalized one of their louche sons in his novel, Tess of the d’Urbervilles.

Enough of the famous and infamous. The millions of ordinary people, ignored by history, are just as important, although one must delve differently to find them. Their traces remain in the shadows of ridge and furrow ploughed across the fields, the remains of pottery thrown out of badger setts. They may have been tied to the land in small villages, but they were also connected to towns, markets, and the great centres of pilgrimage by the well-trodden roads that still exist today. It was the labour of the ordinary people that built the churches, it was their feet that wore down the threshold stones, their sharpened arrows that left grooves in the doorways, their candles, lit in chantry chapels, that willed the souls of this volatile region through Purgatory to Heaven.

On the surface, this land certainly pleases the eye. It has hills and valleys of extraordinary beauty, views of distant mountains, sunken tracks roofed by trees, forested banks covered in bluebells and orchids, the colours of heather, of autumn trees and spring flowers. Church towers rise benevolently through the landscape. The ruins of castles welcome and also repel with their harsh promise of romance.

But go down a layer, or two, and there are stones and iron, bones and blood. There is ambition and feuding, love and greed, treason and artistry. It is these things that excite the imagination of a writer, that keep my heart racing to finish a story about a little known time in this very particular place. A place of many parts: ambiguity, contradiction, paradox, and paradise. It is no accident that so many artists and entrepreneurs have chosen to live here, and never to leave.

Our ambitions are alive and well in the Marches.

Kate’s second medieval novel set in the Marches, All the Winding World, (sequel to The Errant Hours) was published in June 2018.

www.kateinneswriter.com / @kateinnes2