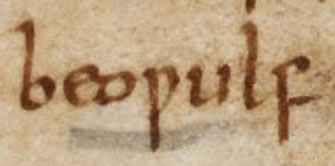

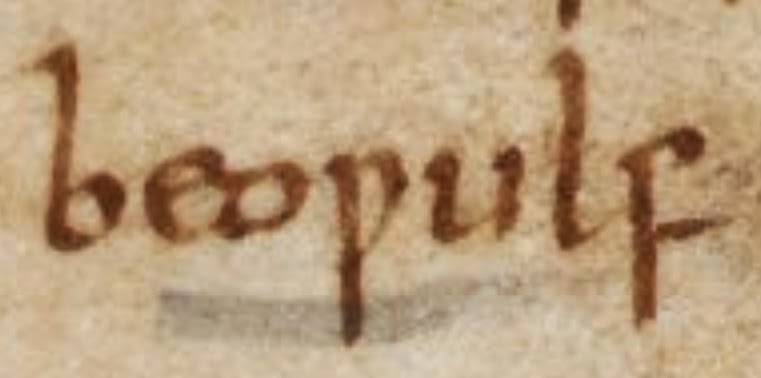

From the Beowulf Manuscript, BL Cotton MS Vitellius A. XV, f.132

Sometimes a poem comes to me, and it is like meeting an old, dear friend unexpectedly. But sometimes a poem comes, and it is like walking into the kitchen in the morning to find that my pet collie has transformed into a savage wolf overnight.

Just such a poem came from my innocent exploration into early English poetry. I was already familiar with the story of Beowulf. As a child, I had a book about heroes and mythology which contained some wonderfully gory pictures: Beowulf with Grendel’s severed arm, and even more intriguing, the monster’s mother, fiercer than her son, fighting with Beowulf in her underwater cave.

A warrior fighting a female monster in the 13th century Icelandic Saga

Certainly Grendel and his mother were portrayed as monsters, and have been in most retellings of the tale. Grendel is a night-goer, a shadow-walker (sceadugenga). He and his mother are said to descend from Cain, the first son of Adam and Eve, and the first murderer. They move ‘beyond the pale’ in Seamus Heaney’s translation, and he refers to her as a ‘monstrous hell-bride.’

It was only when I started to look into the original that I discovered that the word used to describe Grendel’s mother, anglaeca, is also used to refer to Beowulf himself. Some scholars believe that it should be translated as ‘fearsome’ or ‘warrior’ rather than ‘fiend’. In the Beowulf manuscript, she is referred to as an ‘ides’, a respectful way of saying ‘lady’. Elsewhere she is simply called merewif, a woman of the mere. Perhaps there was a territorial dispute about land use at the heart of this conflict between the mead hall and the mere.

Whatever she is or was meant to be, her words came through very strongly as I wrote. This voiceless character had things she wanted to say. Principally she wished to offer Grendel some advice. He ignored it, which is every child’s prerogative.

The alliterative style is typical of early English poetry.