|

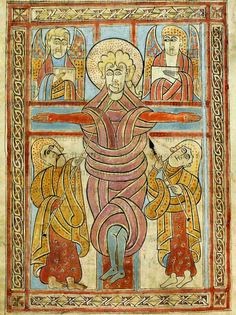

| Crucifixion from the St Gall Gospels Irish, 8th century, Abbey of St Gall Cathedral Library, MS 51 (One soldier offers Jesus vinegar on a sponge, the other makes ready to pierce his side with a spear.) |

According to the New Testament sources, Jesus was crucified on Golgotha, ‘the place of the skull’. Scholars are in disagreement as to whether it accrued this name because it was a place of execution, or if the rock formation had the appearance of a skull from a certain vantage point and was therefore deemed an appropriate place for killing. In any event, the exact location is disputed. I myself favour the theory that the location is a hill just outside the walls of Jerusalem, within sight of the temple, which looks like a human cranium. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Calvary

Unconstrained by facts or lack thereof, Christian artists have approached this place of death with both convention and originality. Early Crucifixion images were characterised by the serene acceptance of Jesus on the cross. This was the representation of Jesus as God. He was pictured against a heavenly backdrop, gold or sometimes blue, and on earth indicated by highly stylised rocks. Almost always, just below the cross with its polite drops of blood, there is a skull, and some other human bones.

|

| Vannuccio Crucifixion with the Virgin and St John the Evangelist 1387-8, Philadelphia Museum of Art |

The indication of this place becoming a battle ground between heaven and earth is accentuated by the inclusion, in some cases, of angels and demons.

In most representations of the crucifixion, Mary, Jesus’ mother, and John the Evangelist stand near the cross- an allusion to Jesus’s wish that they should look after each other in John 19:26-27.

There was a gradual increase of the expression of Jesus’s suffering over the second millennium AD, emphasising Jesus as Man. As the representation of Jesus’s humanity increases, so too does Mary’s. By the 15th century she has lost her stoic sadness and she faints with grief and horror. This accentuation of human emotion has an interesting, perhaps unpredicted, effect.

The more his human struggle is shown, the more people are able to ‘identify’ with Jesus, and, potentially, he with them. But the more human Jesus appears, the less god-like he is, and the more fragile is the faith that proclaims him divine. In that thin layer of painted skin that gives his expression sadness and pain, we recognise our own weakness, our inevitable failing, our eventual destruction.

Twenty-eight years ago I became aware that the Gospels were describing the life, torture and death of a political prisoner, one who had a radical religious message which threatened the power structures of his society. At the time I was involved in Amnesty International and just becoming aware of the horrible creativity expended on torture, whether by direct or indirect means.

The reason that the Christian church adopted the cross as a symbol of its faith intrigues me. The images of the crucifixion, and all the events surrounding it, vastly outnumber representations of the Easter resurrection in Western art (although the nativity scenes of the Virgin and Child do offer a counter balance). It seems almost gratuitous.

As a species we are fascinated by, and terrified of, death. As far as preoccupations go, it almost outweighs sex. We are interested principally in the death of others, not our own. Denial of the inevitability of one’s own death coexists with this fascination. Perhaps we are adapted to pay so much attention, so that we learn how to avoid our own death for as long as possible.

Millions of people have died in agony, deliberately, at the hands of other people. It is not Jesus’s death that makes him a powerful religious symbol. It is his choice of death rather than life. Maximillian Kolbe, a Polish Franciscan friar in Auschwitz, was inspired by Jesus’s self denial to put himself in a condemned prisoner’s place. The man was being sent into a cellar to die of starvation (retribution for the escape of three prisoners), but he cried out in grief for his family and Fr Kolbe chose to go in his place, dying so that another should live.

From acceptance of death, life emerges. Spring arrives. Life and goodness triumph.

Hold on to that thought while you read this rather depressing crucifixion poem.